_Kennedy Horton is a sophomore at MU studying English. She is an opinion columnist who writes about student life and social justice for The Maneater. _

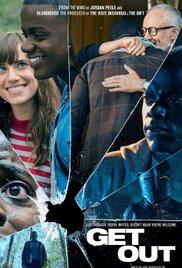

I’ve seen _Get Out_ twice since it’s been in theaters. I already think it’s going to be the best movie of 2017. It’s a black-created and -directed film by Jordan Peele, best known for his role on the comedy sketch show _Key and Peele_.

The movie is a commentary and demonstration of the black experience. It shows the frightening reality of being a person of color, specifically a black person in America. It also demonstrates the frustration and silencing effect institutional racism has on its victims. Peele does this through a seemingly innocent visit by Chris, the black boyfriend, and Rose, the white girlfriend, to Rose’s parents’ home for the weekend. It is a genius movie that all people, no matter what color you are or what your favorite genre is, should see.

It’s terrifying in the best way — in the way that a cold splash of water is jolting, but it wakes you up. The film gets the job done. I couldn’t sleep very well after my first time seeing it. Horror films usually have this effect on me, but it wasn’t because it was so scary. As in, there weren’t clowns popping up or dark figures in corners or anything like that. It was more perturbing than anything else. It gives the same chill you might get from watching “The Shining” or “Misery,” those movies that twist your gut because they teeter on reality. That’s the genuinely horrifying part. I was on edge for about a week. And then, of course, I saw it again.

There are so many layers to the film. It’s a movie you watch, read an article about, watch again, mull over, read another article about, watch an interview about, and so on. It’s constantly unraveling into this bigger picture that I can assure you you did not see the first time watching. It’s like those Russian nesting dolls — there’s always one inside the other until you get to the smallest one. Or, it’s like a puzzle that’s all put together except for a few pieces. You may think you see it all, but you have to look under the couch and back in the box one more time to get every piece.

Not only is it intricate, but it is done in such a clever way. In some movies, there are lines and scenes that are filler, just taking up space to get us to the next important scene. _Get Out_ doesn’t have any of that. Every single line in every single scene is a cog moving us to the climax. Even post-climax, where stories can sometimes rush to wrap things up, Peele doesn’t. Everything is deliberate.

It’s a movie that makes you contemplate. Personally, most of my thoughts were focused on the portrayal of the film because the content — racial microaggressions, racial stereotypes, cultural appropriation, being the only black person in a space — are all things I can relate to. I don’t have to put myself in Chris’ shoes because I’m already in them. I imagine, though, that for someone who isn’t black or another person of color that it really forces you to be in the other guy’s shoes. It forces you to ponder whether the things you say and/or do are as innocent as you think they are. It’s a very thought-provoking movie that will call into question your own biases. It’ll make you think about where you stand or if you stand at all in this racially charged world. And it’s OK if it makes you uncomfortable. Real change doesn’t come unless we’re out of our comfort zones.

The movie isn’t an attack or something intended to offend anyone. It’s someone’s story, someone’s experience. We don’t get to tell someone that their narrative is an attack just because we don’t like it; a person’s perspective can’t be negated. What’s compelling to me is that at the end of the movie, everyone of every color is rooting for and identifying with Chris, the victim, and against the family, who represents institutional racism. It makes you wonder: If we wouldn’t want it to happen in a movie, we shouldn’t act like it doesn’t happen in real life.