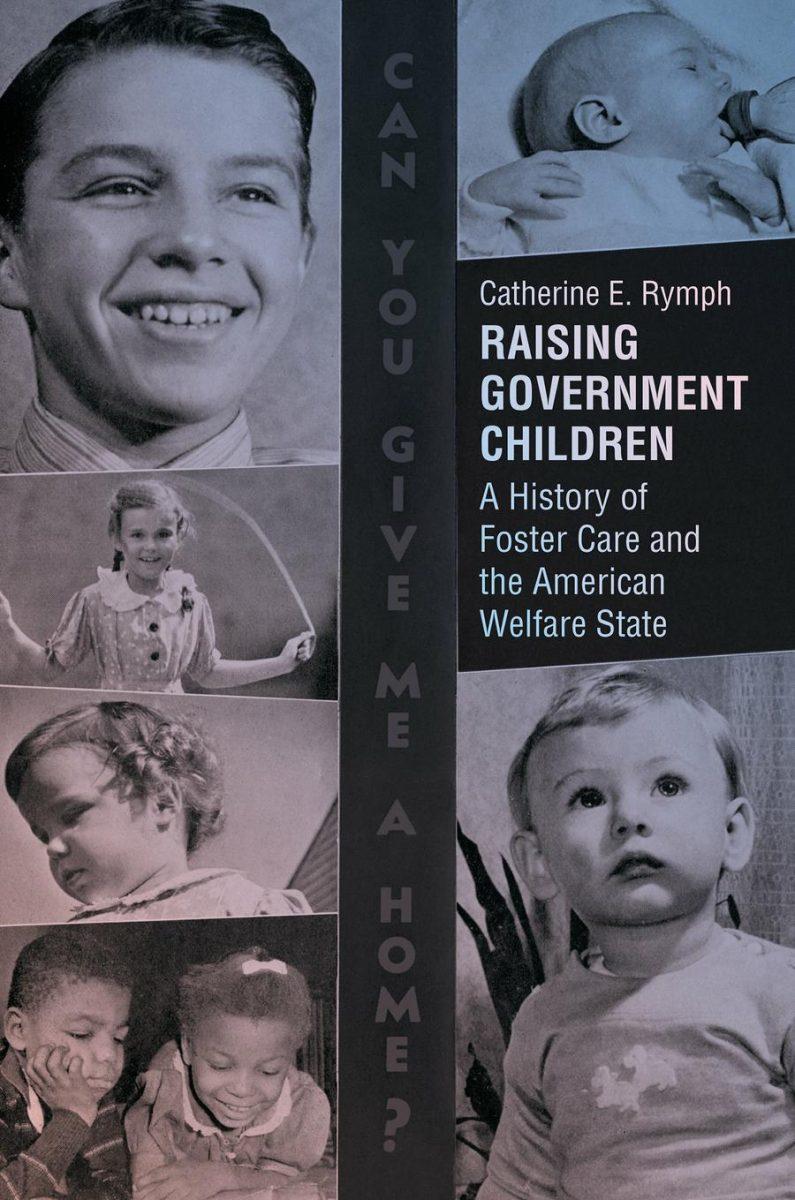

Associate history professor Catherine Rymph’s new book, “Raising Government Children: A History of Foster Care and the American Welfare State,” details the history of the 20th century foster care system in America and will be released this October.

Introduced to the subject through having family members connected to the system, Rymph’s second book is the first to document one of the country’s more hidden fractions of the welfare state.

“I wanted to know something about what it was like in the past because I knew a little about what it was like in the present,” Rymph said. “I tried to find a history of the system, but there was no history.”

A nine-year project, Rymph’s research follows foster care’s evolution beginning with its formation in the 1930s through the end of the 1970s.

Two archival collections make up most of the primary sources that shaped the book, one of which includes the standard practices of foster families documented by the Child Welfare League of America.

The second collection is from the records of the Children’s Bureau and includes letters sent by mainly women involved with the system. Written by both mothers and foster mothers, the letters often asked for help in various situations.

“I got a lot of really gripping, really personal firsthand accounts of this subject, which I didn’t expect to find,” Rymph said. “Case files are all closed to the public.”

Rymph said these letters made it possible for her to tell a more “human” story.

“I think currently there are a lot of negative feelings about foster children and foster parents,” Rymph said. “One of the things I tried to do in this book is help people try to understand what this system is like for them.”

Her work explores the functional problems of having a social welfare provision subsidized through private families and how lack of funds along with overworked caseworkers have always added to inherent flaws.

“There was never some period in the past when people thought [foster care] was working well,” Rymph said. “It’s always been a system that no one thought really served the children it was supposed to serve.”

Graduate student Sean Rost assisted Rymph in some of her research by searching through newspaper advertisements and classifieds that mentioned foster care from various cities over the course of two semesters.

“She gave me the guide points for the research, but she thought I would be looking for a needle in a haystack,” Rost said.

After uncovering various pieces of information, the two continued to email and meet to share sources from new cities as they continued their search.

Rymph’s colleague, postdoctoral teaching fellow in history Cassandra Yacovazzi, assisted in the completion of the book’s index and appreciates how the book illustrates the “complexity” of the foster care system.

The work includes research examining how gender roles and unfulfilled expectations of how the welfare state would be today have each played their part in where the program now stands.

“Dr. Rymph’s work has really changed my perspective on the origins and development of foster care and the very hopeful and optimistic approach that those who developed [the foster care system] had,” Yacovazzi said.

Yacovazzi said the book touches many people’s lives, even those with no connection to the system directly.

“Her book raises the question of what our responsibility is to the community and the children in the community in which we live,” Yacovazzi said.

Rymph’s own personal attachment to the topic has made the research and creation of the now-finished product even more illuminating.

“It’s helped me to think a lot about how things have changed, what’s at stake really,” Rymph said.

The book is being published by the University of North Carolina Press and is available for pre-order on its website as well as on Amazon.

Rymph will speak Oct. 20 at Jesse Hall 410 at 3:30 p.m. as a Kinder Institute Faculty Advisory Council member about her new book. The event will serve as both a part of Kinder Institute’s colloquium series and a launch party.

“I certainly hope that people who read it will think more about what foster care means and what foster parenting means,” Rymph said. “I think it’s a lot of people trying to do their best in an imperfect system.”

_Edited by Olivia Garrett | [email protected]_