_Bryce Kolk is a freshman journalism major at MU. He is an opinion columnist who writes about politics for The Maneater._

It may feel as though it wasn’t long ago that Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton faced off against each other for authority of the highest office in the land. That’s probably because it wasn’t.

Several candidates have already announced their candidacy for the 2020 presidential election. Though we’re still nearly two years out from the actual election, the 2020 election cycle is well underway.

The length of our campaigns is a problem and it’s getting worse.

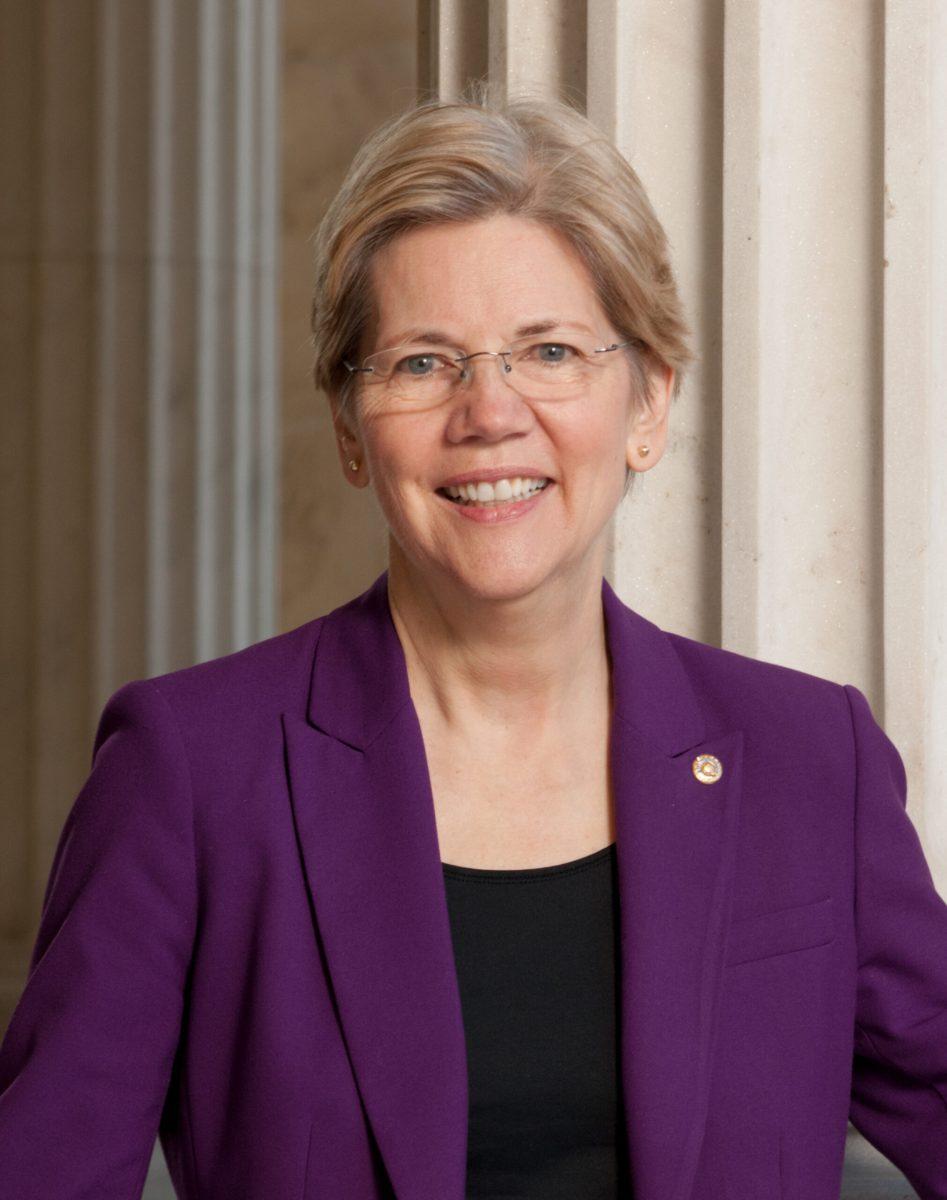

Democratic Sen. Elizabeth Warren kicked off the cycle by announcing her campaign on New Year’s Eve, 673 days out. Republican Sen. Ted Cruz announced his candidacy 596 days from the 2016 election, becoming the first major candidate to announce.

Our campaigns are a marathon compared to other countries.

The 2015 national election cycles in the U.K. and Canada were just 139 and 78 days respectively. In Mexico, the campaign length is set at 147 days by law. Japan’s campaign season, also set by law, is barely even a sprint at just 12 days.

Political pundits and junkies may love the long American election cycles, but these marathon campaigns can do a disservice to society as a whole. When it feels like there’s always an election around the corner, political division never seems to fade.

The 2016 election was bitter and left Americans more divided among party lines than ever. While party loyalty is nothing new, that division has been pervasive. The rift of a Left America and a Right America is extraordinarily present even now — two years into a new administration. It’s one thing when the body politic divides, but it’s another when we lose empathy over party lines.

We also blew $2.4 billion on the 2016 presidential election. Without an insane sum of money, it’s nearly impossible to be competitive in a presidential campaign.

Parties in the U.K. are only allowed to spend $29.5 million total in the year before an election. In 2016, Democrats spent $768 million on Clinton alone.

Candidates have nearly two years to raise and spend funds. This puts smaller candidates with little fundraising ability at an immense disadvantage right out of the gate.

National campaigns tend to overstay their welcome and exhaust voters.

Fifty-nine percent of voters felt worn out by election coverage in July 2016, a full four months before the campaign would end, according to Pew Research Center.

Making a law defining the length of our national campaign season is the simplest way to shorten the cycle. Trimming it down to six months could help reduce the fatigue felt by voters, but still maintain their ability to be informed.

This six month window would be much closer in duration to local campaigns. For example, Columbia’s mayoral campaign began in late October and will end on April 2, after the election.

Moving primaries down the calendar would be necessary to accommodate this time-table.

Rather than having the primary season last from February to June, have it be only the month of September. This could allow candidates four months to campaign before the first primary vote is cast and would give the full month of October for each nominee to campaign before the General Election.

Shortening the primary season would also lower the significance of the first few state caucuses and primaries. As of now, candidates spend much of their energy, and money, on states like Iowa and New Hampshire, because of the increased media coverage of these beginning contests. This would force candidates to see the primary map as a whole.

While the jump to a six month election cycle may feel drastic, it’s still longer than most other countries. It would make the process less exhausting for voters, and could force candidates to campaign in every state.