Columbia is home to many properties that have passed through several hands of ownership, some changing and some preserved to be as exactly as they were 100 years ago

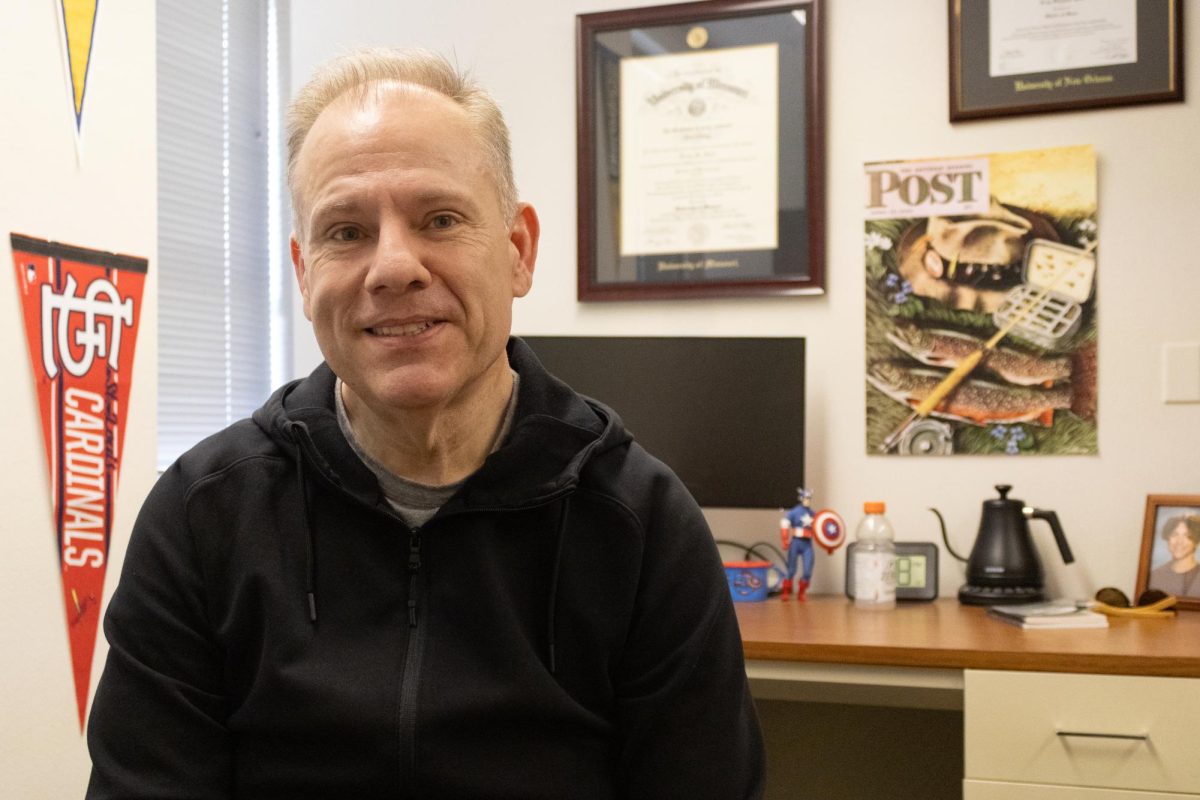

Tanner Ott

People walk up and down the streets of Columbia every day — from getting a bite at Shakespeare’s to seeing a film at Ragtag Cinema, each of these buildings are full of history that spans over a hundred years. Often homes are used as historical landmarks, and Columbia is full of houses and commercial buildings alike with history that residents don’t often get to see.

Tanner Ott, a project manager at Alley A Realty/Ott Historic Rehab, works to restore Columbia’s storied properties.

Ott has worked on downtown property restoration since 1986, and has revived the venues that now house the Paramount Office Suites, Bangkok Gardens and Ozark Mountain Biscuit Co.

“We take an old building and really gut it and remodel it,” Ott said. “Sometimes in each case, we would try to find out what the building was designed for and how it looked and bring back as many elements as possible.”

Restoring these properties is no easy feat, but Ott finds fulfillment in the more difficult aspects of historical restoration.

“Sometimes there’s structural components where it makes it a little more difficult to change certain things or open things up,” Ott said. “But it’s always fun trying to use the framework of an existing building and try to form our perspective. We look at, ‘How can this meet today’s demand for businesses downtown?’”

Ott also believes that it is important to hold onto the ideas that the original architects had for these buildings instead of demolishing them.

Ott’s work in preserving historical properties in Columbia goes to show just how rich in culture and history the city is and how even in changing what goes on in a building, its history will always be there.

“The character and culture that has made Columbia so great over the years remains to tell new stories and be home to new businesses,” Ott said.

Blind Boone Home

Built in the late 1880s and purchased by the City of Columbia in 2000, The Blind Boone Home was home to John William “Blind” Boone, an African-American musician who greatly influenced American classical and ragtime music of the late 1800s and early 1900s. Boone, who was blind, had an incredible ear for melody and was skilled on the piano. The Blind Boone Home currently houses one of Boone’s pianos, which acts as the centerpiece of the home.

Boone lived in the home for the majority of his life and was a major figure in Columbia’s community for the time he lived in the home.

“He was well known as a concert piano player, but he was also very popular in the community,” Olson said. “He was kind of a soft touch and he gave money to help people.” Boone often donated money to the youth in his community as well as organizations — including what is now Columbia College.,

Restored in 2013, the interior furnishings and walls of the Blind Boone Home were recreated to resemble the styles of its original construction as closely as possible. Much of the furniture in the home did not belong to Boone, as most of his furniture was either sold or donated following his death.

“It is one of the few houses that survived urban renewal in the early 1860s and we thought it was important to save it for that reason alone,” Olson said.

The Blind Boone Home is now an appointment-based tourable location that is also rentable for community events like weddings, graduation parties and baby showers. The home also hosts two parties during the year, a Christmas party and a birthday party for Boone on May 17.

Conley House

The Conley House is a two-story Italianate home which stands as one of the oldest houses in Columbia. Once home to Sanford and Kate Conley, local entrepreneurs of the time, the history of the house spans back to 1869 and is rich in both architectural and human character.

While Sanford Conley lived in the home for 20 years, Kate lived there for 50. Kate, despite being referred to as just a housekeeper by records, actually took care of most of the household and business after Sanford’s death.

“She ran the household, which didn’t mean that she just went to the grocery store,” O’Brien said. “She basically operated kind of a mini enterprise.”

Dianna O’Brien is the president of CoMo Preservation, a local nonprofit group formed in April of 2023. For O’Brien, historic preservation is a necessary part of understanding not just the buildings but the people that inhabited them.

“One of our missions is to increase the awareness of the importance of historic preservation,” O’Brien said. “I believe that a building is an envelope for our history, so when we lose a historic building, we often lose the history it contains.”

O’Brien discussed how there was a time when the MU campus wasn’t exclusive to the college and housed a myriad of other unrelated businesses of which the Conleys were included.

“[The Conleys] were in dry goods like flour, so they weren’t involved in the campus at all but they were on the campus,” O’Brien said.

O’Brien believes greatly that preserving historical buildings means preserving truth.

“It’s historically relevant because it keeps us factual about our past,” O’Brien said. “It closes off our ideas and our opportunities when we don’t know our history.”

CoMo Historical Preservation meets once a month and the meetings are open to the public. Alongside this, O’Brien will be conducting free walking tours of historical movie theaters in June. O’Brien has also written a novel on these historical movie theaters titled “Historic Movie Theaters of Columbia, Missouri” which details cinemas like the Tiger Theater.

“I don’t walk downtown and see the buildings that are there; I see the 1928 movie palace,” O’Brien said. “I see what was there, so it makes for a much richer experience.”

Tiger Hotel

The Tiger Hotel was once the first and tallest skyscraper between St. Louis and Kansas City, Mo. When the hotel was built in 1928 by architect Alonzo Gentry, the red-brick building had 10 stories and over 100 rooms, serving as a place of comfort for townies and tourists alike.

Today, the Tiger Hotel’s exterior remains relatively unchanged, but the interior has taken on many forms since its opening day. In 1987, bankruptcy forced the hotel to convert to an assisted living center called the Tiger-Kensington. It would then become a banquet hotel in 2003 after being purchased by Tiger LLC, prioritizing ballrooms and event spaces.

The event spaces were soon replaced by additional hotel rooms and the terrazzo floor would be replaced when current owner, Glyn Laverick, purchased the building and put it under complete renovation in 2011. The distinctive glass chandeliers, the layout of the lobby and the neon red sign that says “Tiger” on top of the building still remain in the same condition as they were when The Tiger Hotel first opened.

The Tiger Hotel still aims to preserve the building’s history through requiring employees to know key points about the hotel’s lobby and when it first opened.

Tiger Hotel Guest Representative Thomas Halderman has been working at the building since 2021.

“It represents a sort of preservation of the culture of Columbia,” Halderman said. “Columbia is rapidly growing every year. It’s changing all the time.”

Greenwood Home

In 1834, a family from North Carolina called the Lenoirs moved to Boone County. By 1839, they turned a building that was once in ruins into a two-story red brick home that took on the federal style architecture known as the Greenwood Home.

Greenwood functioned as a plantation home where the Lenoirs enslaved people and indentured servants. For as old as the home is, Greenwood remains to be in good condition with six original, ornate fireplace mantels.

“I think just about everybody who owned this house really wanted to take care of it,” current homeowner and resident Julie Plax said. “So it’s been in the hands of people who like old houses and are willing to take on that task.”

Plax discovered the Greenwood home when she was going to school in Columbia in the 1970s. One of her acquaintances lived in the home, and Plax often reminisces about the parties she would go to that were being hosted at Greenwood. Plax said the large yard made them feel like they were secluded and living in the country, when really they were right behind the Gerbes grocery store.

When Plax was looking for homes in the Columbia area five years ago, she said her memories from the 1970s brought her right back to Greenwood.

“I had been in the house and thought, ‘Gee, I’d like to live there someday,’” Plax said. “And when it went on the market about five years ago, I bought it.”

When Plax moved into Greenwood, the previous owners left her a scrapbook showcasing the home’s history filled with personal letters from people who once lived at Greenwood, including the Lenoir family. She learned that Slater Lenoir, one of eight of Walter Raleigh Lonoire’s children who grew up in the Greenwood home, got married and built the Maplewood House — another historical home in Columbia.

The Greenwood home is on the National Register for historical places and is considered one of the oldest homes in Boone County. Plax said she wants to preserve the home’s history by sharing its significance in the community to the people of Columbia.

“If anyone ever shows an interest in the house, take them around and give them a little tour.” Plax said.

Edited by Alex Goldstein | [email protected]

Copy edited by Emma Short and Grace Knight

Edited by Scout Hudson | [email protected]