MU Libraries lost 20% of their journal collection at the end of the Spring 2021 semester because of the rising prices of keeping those journals in libraries.

MU Libraries spokesperson Shannon Cary said that MU works with library groups to find the best price for journals. Then, both parties agree on how they can be used through a licensing agreement.

Increasingly, however, publications are sold in bundles. They sell in bundles charged at a steeper price, making it unaffordable for universities.

In this case, Ellis Library suffers a hit to their selection because new materials have become too expensive. MU has several programs which require students to do their own research using academic journals. Jon Stemmle, a professor in the School of Journalism, said that graduate students need scientific journals to do their research. Even professors use them when putting together theses and dissertations for graduate students. Stemmle said losing access to scientific journals is ultimately detrimental to both professors and students.

Cary said that in order to earn tenure as a professor, you must be published in a peer-reviewed journal. When an MU professor gets published, this means that the university no longer owns this intellectual information — the publisher does — which leads to the library having to “buy back” their own research.

There isn’t a great deal of diversity in publishers either. Cary said many of the smaller publishers were bought up and conglomerated into much bigger companies. One of the biggest of these is the company Elsevier; which publishes over 60 journals and 560,000 plus articles.

Elsevier reported a 37.2% operating profit (how much a company makes on a dollar of sales after other factors such as wages and materials are taken out) in 2019, higher than Apple’s 24.5% and Alphabet Inc.’s 21.4%.

For the companies that are raising these prices, such as Elsevier, the scientific journals are extremely profitable.

According to a 2017 Guardian Article, “scientists create work under their own direction — funded largely by governments — and give it to publishers for free.”

This makes the journals more profitable, as the publishing company pays for neither the publishing rights nor the actual research.

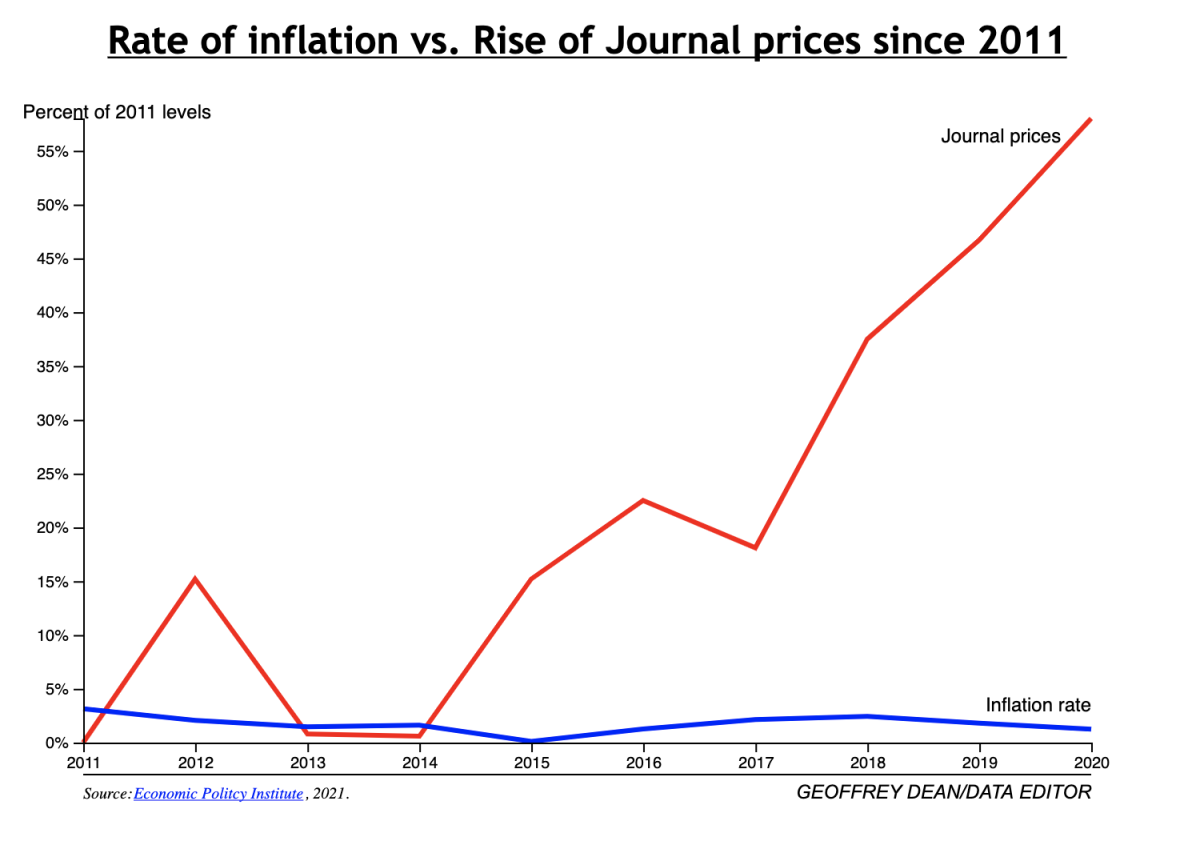

As publishing companies hike the price of scientific journals faster than the rate of inflation by a margin of nine percent, it can be difficult for universities to catch up, causing more students to turn to illegal pirating sites. By contrast, there are fewer companies than ever controlling a greater portion of the information online.

“Because Elsevier owns so much of scholarly communication, they can set the prices as they wish,” Cary said.

This essentially means that three or four publishing companies have a monopoly over the entire academic publishing industry — making it more difficult to dispute prices for universities around the nation, including MU itself. MU Librarian Rachel Brekhus said writers work hard to produce their researched work and are sometimes made to pay to get it published, and then another additional fee is charged to libraries. All these fees add up to librarians having to do more than their share of work trying to keep a large selection of journals still readily available.

“[Universities] have to find a way to work with publishers other than the ones that have broken our faith time and time again,” Brekhus said.

Recently there has been a trend of universities doing just that. The University of California dropped all subscriptions with scientific journals after talks fell through to get what they viewed as a fair price.

“I think you’re going to need to see more actions like the University of California did,” Stemmle said. “I think you need universities to actually stand up and say ‘Hey, I’m not paying.”

Edited by Emmet Jamieson | [email protected]