Content Warning: This article discusses racist violence in the American South during the 20th century.

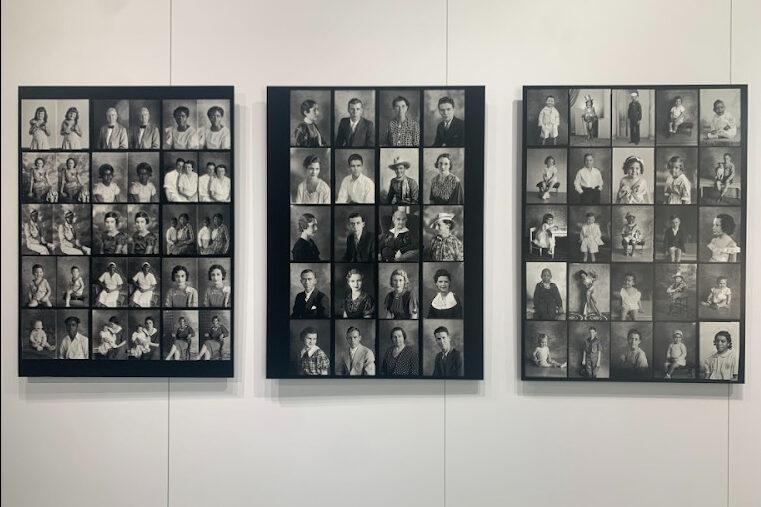

Otis Noel Pruitt spent over three decades meticulously photographing life in the town of Columbus, Mississippi, (locally known as “Possum Town”) from the 1920s to the 1950s. Berkley Hudson, an emeritus distinguished MU professor, also spent over three decades meticulously archiving, researching and drawing attention to those same photos.

Pruitt and Hudson’s intersecting goal to holistically present their hometown is the basis of the exhibit “Mr. Pruitt’s Possum Town: Trouble and Resilience in the American South,” on display at the State Historical Society of Missouri now through Nov. 5.

“I love that you can take any of the pictures and that there are these webs that go out from it — from the past to now,” Hudson said.

Hudson’s passion for the Pruitt collection is amplified by the fact that he is from Columbus himself. One of Hudson’s earliest memories is of Pruitt photographing him and his family in the 1950s.

With over 90,000 negatives and sparse context, the Pruitt collection is no small archival feat. Hudson and four childhood friends acquired the photos in 1987 after a decade of attempts to purchase them from Pruitt’s assistant, Calvin Shanks. Following Shanks’ death, boxes upon boxes of Pruitt images sat in the loft of a Columbus local’s hardware store. After saving them from a future in the shadows, Hudson embarked on an ongoing journey to archive and showcase the photographs.

“We realized this was a visual storehouse, a photobiography, of our town,” Hudson said. “In visual ways, telling a story that hadn’t been told in any other way. Not only telling the story of our town … it spoke also to what was going on throughout the South during the time of Jim Crow and racial segregation.”

Hudson estimates he’s sifted through around 20,000 of the nearly 90,000 images. Rather than taking a nose dive into all of them at once, Hudson prefers to drink from the collection slowly. Focusing on small increments, Hudson works to find names, backstories and descendants of the subjects.

Hudson published a book of his findings, “O.N. Pruitt’s Possum Town: Photographing Trouble and Resilience in the American South,” which contains over 190 images accompanied by contemplative essays and captions. Since Hudson procured the collection, he has aimed to archive, research and eventually exhibit the photos.

The exhibit includes a slim curation of 100 images, with 25 of those photos on display in the Reynolds Journalism Institute. The tight selection expresses the depth and vastness of Pruitt’s photography, while also enabling visitors to closely consider the detail of each photograph.

“The family pictures, community pictures, open up doorways where there are imaginable and unimaginable stories and experiences … that can enrich your understanding of your own life, the lives of the people who you grew up with and the lives of people different than you, who you didn’t grow up with,” Hudson said. “But we have to be willing to slow down and do that and undertake that process. And sometimes that process can be painful.”

Six of the exhibit’s most painful images are concealed behind a curtain. These include photos of minstrelsy, an execution and a lynching.

“These images need to be seen, we can’t hide them,” Hudson said. “People need to understand the history. But it’s also important to have the ability to opt in.”

Growing up in Columbus, Hudson never learned about the lynchings that occurred there despite Mississippi having the highest lynching rate of any state in the United States between 1882 and 1968.

Missouri has unavoidable ties to the racial terror depicted in the Pruitt collection, with 69 documented lynchings in the state between 1882 and 1968. Two of these documented lynchings happened in Boone County. The first was of George Bush in 1889, and the second of James T. Scott in 1923. Both were awaiting trials in Boone County Jail, which they never received. Hundreds of Columbia citizens participated in the mobs, yet no one was convicted of murder in either case.

Many of Pruitt’s photos document and confirm impressions of the American South, but his photos also challenge perceptions of race, gender and sexuality.

One such image depicts a baptism in the Tombigbee River, with both a Black and white group present. While the groups stand separately, the image offers a unique insight into religious settings of the early 20th century.

Another image depicts two women, extravagantly dressed as a bride and groom, participating in a junior-freshman “wedding” tradition at a Mississippi women’s college.

Other images, like a haunting image of a young child standing in a crowd with a bloodied nose, beg the viewer to connect the dots on their own, calling their personal perceptions and history to the forefront.

Hudson had no specific answer for which of the photos he would most like the context behind.

“I like that it’s just mysterious. I’ve been trying for 35 years,” Hudson said. “But at this point, I just go with the Barbara Norfleet line: ‘Photographs are better at raising questions than answering them; they can reveal what you do not understand, and also what you take for granted.’”

Edited by Lucy Valeski | [email protected]

Copy edited by Mary Philip and Jacob Richey