Two photographers form a surprising friendship and an unsurprisingly lovely documentary

As a photojournalist of 10 years, Danial Shah deals exclusively with what is real. The subject of his documentary “Make it Look Real,” Muhammad Sakhi, works in a photo studio in Pakistan where he photoshops photos for his clients. In turn, he deals with what is fake — but maybe not exclusively, depending on how you look at it.

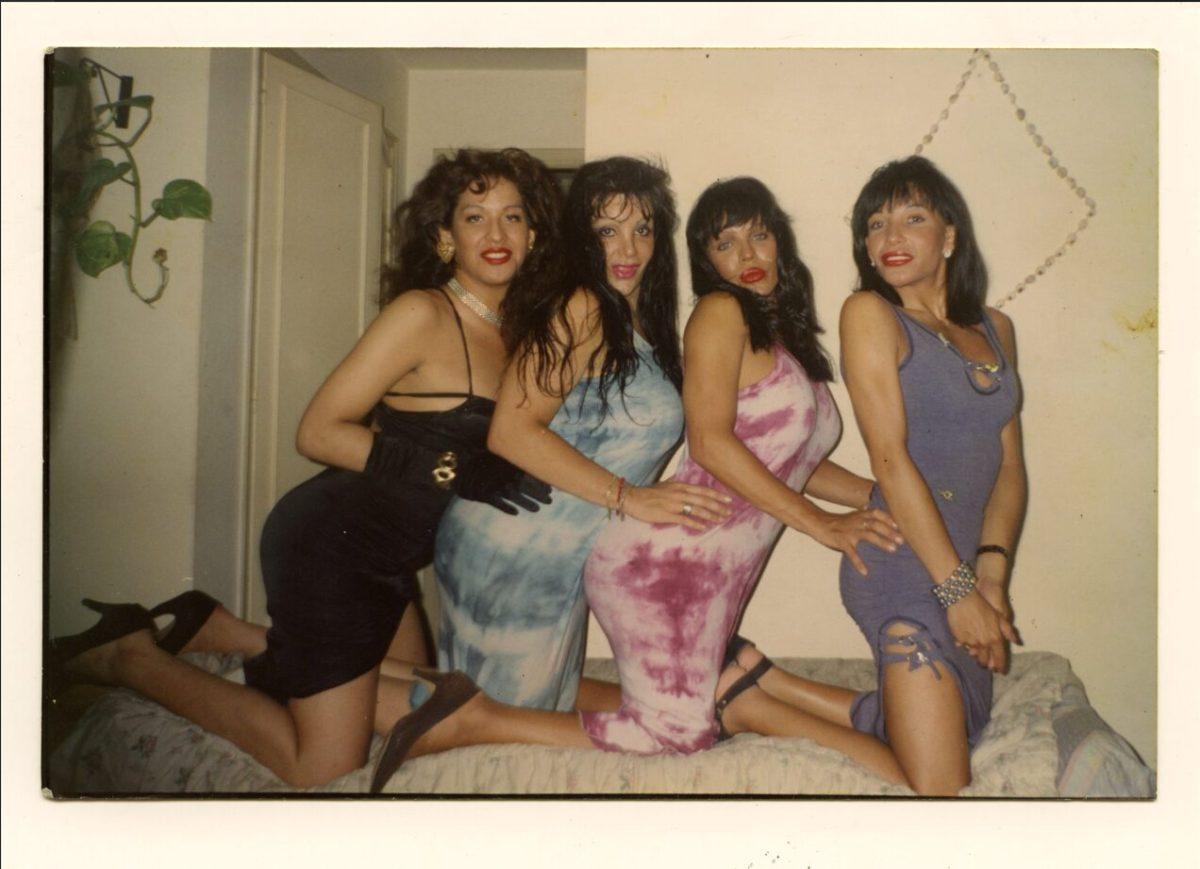

The subjects of Sakhi’s pictures sit in front of a plain curtain on a small bench and walk out with portraits of themselves holding girls and guns, sitting on horses and expensive cars. The film does not approach these clients with any judgement, but rather explores their reasoning behind the falsified photos.

In the documentary, one man asks Sakhi for a photo holding a machine gun in the middle of a military camp. He said he wants to look like a member of the Taliban. Does he think the photos will fool anyone, Shah asks? It’s not for anyone else, the client replies, it’s for myself.

Three young boys come in asking for photos with their faces on buff, adult bodies in expensive suits. Sakhi asks them if they want girls photoshopped into the photo and is met with a chorus of no’s. You’re going to get us in trouble, they half joke with him. They pass their photos amongst each other, with very real joy on their faces.

The photos may be fake, but the desire and delight behind them is fact.

The clients come in and out of the shop — and the film — with Sakhi sitting in the center of it all. He is assertive in his direction of the customers, but always generous and kind. He makes tea for anyone who asks in the market that he works in, as well as for Shah.

Shah takes a relatively large role in the narrative, choosing to include his questions and conversations with Sakhi in the film. In fact, the documentary opens with the two photographers taking turns focusing the camera as the other sits in front.

Many documentarians remove themselves as far as possible from the subject of their work in an attempt to be professional and not interfere with the unfolding of events. Their films are the better for it. In the case of “Make It Look Real,” Shah’s presence enriches the movie tenfold.

Shah has said he didn’t want to make the movie some “exotic” enterprise, where an outside eye alienates its characters. By inserting himself in the narrative, the friendship between the two photographers makes the film feel personal and empathetic.

Throughout the film, Sakhi mentions that he’s saving up money to pay smugglers to get him out of Pakistan for reasons such as the intermittent bomb blasts and the persecution of the Hazaras. In the end, he decides he’ll settle for a vacation. The money from the photo studio is good, he says, and he likes home.

The photo studio Sakhi worked in has since closed because of a rise in mobile phone usage. Now, he works odd jobs to fuel a renewed desire to permanently leave Pakistan. The film omits this, ending on the positive note and an animation of photoshopped pictures of both Shah and Sakhi.

The artistic choice helps solidify the documentary as the digital version of a warm cup of tea, much like the ones Sakhi makes. It is as hopeful as the clients walking into the shop and is all the better for it.

You can keep up with The Maneater’s 2025 True/False Film Fest coverage here.

Edited by Molly Levine | [email protected]

Copy edited by Hannah Taylor | [email protected]

Edited by Annie Goodykoontz | [email protected]