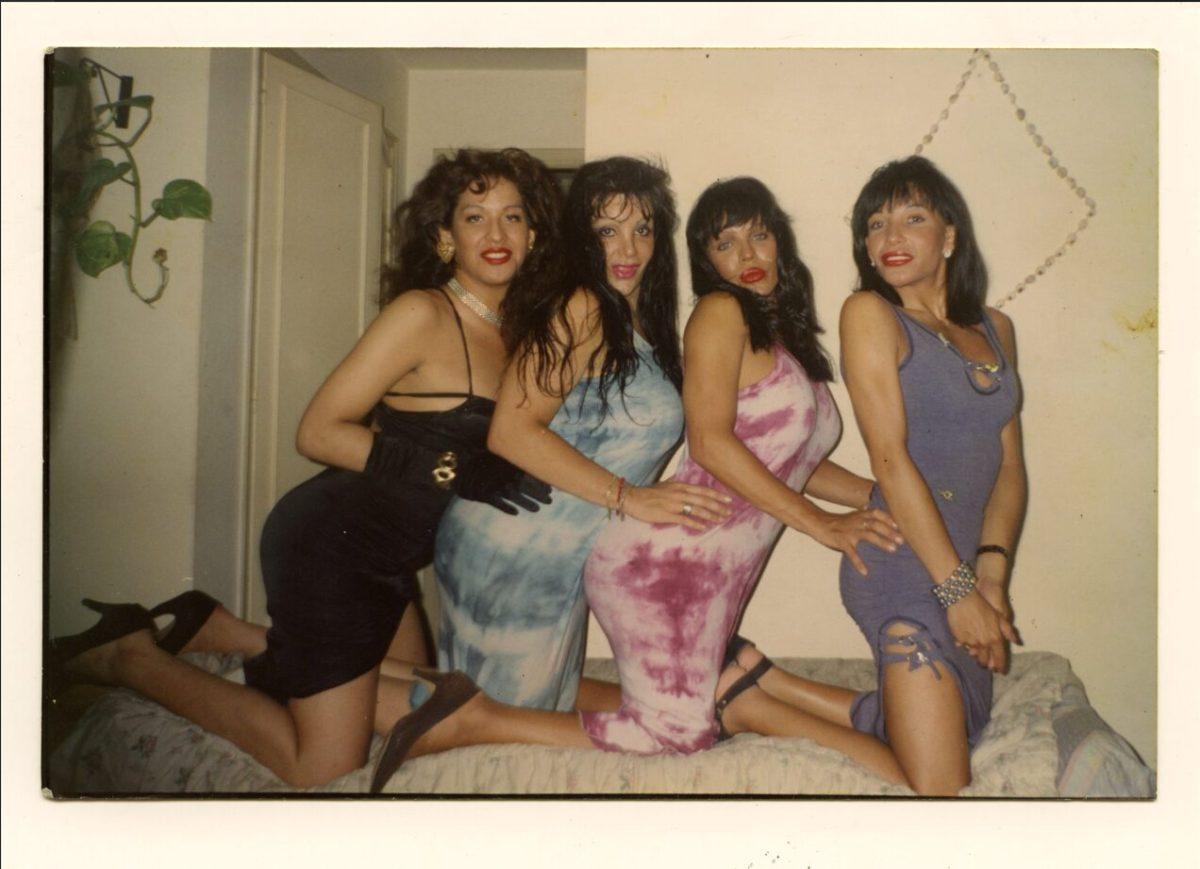

Filmmaker Hu Sanshou returns to his grandparents’ home in Xiangzidian village to capture his family and neighbors’ stories about the Great Chinese Famine

Director Hu Sanshou’s 2013 documentary “Mountain Village” was screened on Friday at the True/False Film Fest as a part of this year’s True Vision Award, the only honor given by the festival. The award is given annually to a filmmaker who is dedicated to the advancement of documentary filmmaking.

The film is an intimate exploration of Sanshou’s return to his grandparents’ home in Xiangzidian Village, in the Shaanxi province of Northwestern China. He conducts personal interviews with his grandparents and their neighbors as they recall their experiences during the 1959-1961 Great Chinese Famine, when millions of people died due to a collapse in agriculture.

During the famine, all of the food in Xiangzidian village was collected by the government and gathered up, cooked and served in a public canteen where each villager would get one scoop of the mixture. According to one of Sanshou’s neighbors, this lasted until 1960 when everyone was instead given their own uncooked portions to prepare for themselves.

Sanshou said in a Q&A after the screening that “Mountain Village” was made when he was studying cinematography at the Xi’an Academy of Fine Arts. For one of his assignments, he was tasked with visiting his hometown and making a film about his village’s experiences during their “three years of difficulty,” a reference to the hardships of the famine.

Because of the small scope of this assignment, the film contains mostly minimalist, still camera shots. Sanshou focuses his camera on a specific subject, such as people working in the village – and lets the audience sit with it for a minute. This gives the film a very personal viewing experience and allows audiences to feel as though they are walking through the village and observing their lives.

The film opens with a shot panning over a long winding road leading to the Xiangzidian Village. Sanshou introduces the audience to his grandparents through simple observations of their day-to-day lives; they feed their pig, chop wood for their stove and knit. As his grandmother speaks about the Chinese tradition of burning ghost notes — paper money — so that their dead relatives can receive them in the afterlife, the film establishes its themes of memory and survival. Through Sanshou’s interviews with his grandparents, audiences are able to build a more personal connection to the filmmaker and his family.

In the first interview of the film, a villager recalls the early days of the famine when their food supply was confiscated by the government. When their home was raided by the military, she remembers the harrowing moments when she and her husband were forced to stand in their house while their child hid upstairs. Graphic details recounted in the first testimony of the film clue viewers into the severity of the famine and build sympathy from the audience.

Sanshou’s grandmother tells of her own experience growing up with the public canteen at only age 7 or 8 — getting a gasp from the audience — when there was often not enough food for all of her family. Her and her great-uncle had to beg house-to-house to get enough food for both of them to eat, while her mother lived on their leftovers. This moment showed the importance of family and how they looked out for each other in adversity. This gives audiences a universal theme to connect with in the film.

In an interview with a villager, Sanshou tells of a time when the mayor of the Xiangzidian village said that the residents were “well off,” despite not having enough food for all of them. She also remembers hearing a story about a man killing his wife and eating her flesh, with his reason being to end her suffering from starvation and to subside his own hunger. In the theater, this moment left many audience members staring at the screen with dropped jaws. This scene exemplifies Sanshou’s use of shock-value through these testimonies to emphasize the scale of how tragic the famine was. This also plays into the film’s central theme of survival, by showing how far people had to go to survive.

In between these interviews detailing the harsh experiences of the village elders who lived through the Great Famine, Sanshou inserts intimate static images of children playing in the streets, workers, a wedding parade and people celebrating at a festival. These shots of everyday life remind the audience that the village endured, while also ensuring that the memories of the villagers who suffered are not forgotten. By using static shots, Sanshou makes audiences feel as though they are standing right there in the village, rather than watching it on a screen.

The one-camera traditional documentary approach gives viewers a very personal look into the lives of villagers who survived the Great Famine. The film has no score and is only accompanied by the sounds of the village and the occasional celebratory songs that they would sing in parades through the city streets. This makes viewers feel as though they are truly watching these villagers live their lives and tell their stories.

“Mountain Village” powerfully ends with a voiceover of a traditional Chinese song while fireworks light up the Xiangzidian village sky as villagers sit around a bonfire. The ending drives home how the themes of remembrance and survival can coexist, as they are able to communicate these harsh stories and still celebrate joy after.

In a Q&A session after the screening, Sanshou said that the film is incredibly important to him because it was his first, having directed it at 19 years old. He said that it memorializes a period special to his life and culture. He ended the session by saying that life gives story to film and film becomes part of life.

Alongside “Mountain Village,” Sanshou screened his newest film, “Resurrection,” and Derek Jarman’s “Blue” — one of the works that most influenced his own filmmaking.

You can keep up with The Maneater’s 2025 True/False Film Fest coverage here.

Edited by Ainsley Bryson | [email protected]

Edited by Ava McCluer | [email protected]

Copy edited by Emma Short | [email protected]

Edited by Annie Goodykoontz | [email protected]