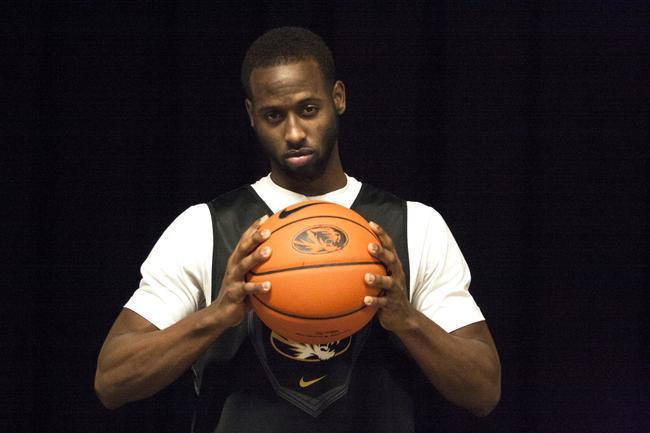

Standing at the tip of the Tiger logo, Keion Bell takes the orange basketball in his right hand and palms it with his left, holding a fire he’s about to unleash upon the world.

As he waits at the center of Mizzou Arena, he sees thousands of fans in store for Mizzou Madness. They’re about to get a taste of the man Missouri players refer to as “a character.” They’ve heard his mixtape and followed his thought-provoking Twitter.

Now they’re going to see his signature move: he’s going to leap over six people for a one-handed jam.

He’s going to show them the side of him he hates the most.

Bell knows what to do because he’s done it before. He performed the exact same dunk act two years ago at a similar act at Pepperdine.

But as he stands on the Tiger, he knows the reason why he left. He remembers how he lost the battle against what always made him so great.

That’s not a worry for tonight, though. In a moment, Bell will be airborne.

The smoke will shoot and the people will cheer. His teammates will go crazy, and SportsCenter will make it the No. 1 play the next morning.

And only he will know how easy the hurdle was compared to all the others.

—–

###“Lack of father figures in our homes / Best believe the ’90s made me, baby”

—–

The chorus of the title track on Bell’s mixtape, The ‘90s Made Me, brings listeners back to the time when he first became what he couldn’t avoid: an individual.

When Bell was 5 years old, his father, Dwayne, was incarcerated on a life sentence. An only child, Bell was left to live with his mother, Sharon Ross. Ross was unable to be reached for this story.

He didn’t learn why his father was going away that day. He still doesn’t know.

“My mom said it’s best if I hear from him, but she hasn’t even told me herself,” Bell said. “My mother did such a good job of being my mom and my father that I never had to ask that.”

For a year or two following his incarceration, Dwayne would call to speak with his son. But at this early stage in Bell’s life, his father was just a stranger.

And so when Bell and his mother moved into a new home, he didn’t want his mom to give his dad their phone number. Bell hasn’t spoken to his father since, although he said he is open to changing that one day.

With no father around, Bell’s mother was home only sporadically, as she was often working to support the family. Bell often felt alone.

“Obviously, that kind of hurt me on the court,” Bell said. “It’s challenging to all of a sudden come from being by yourself and tell yourself what to do to have to get broken and listen to someone else.”

While his mother had to work to support the family, Bell took pride in discovering his talents. First it was singing. Then it was basketball. Later would come the dunking he would someday show the world.

But these talents didn’t only hold the capacity for good. Like all powers, they could mess with the mind. They could create an individual.

—–

###“Sometimes you have to meet someone just like you to know how you’ve been treating other people” — Bell’s “’90s Love Song”

—–

Bell needed people to cheer on his performances and show him ways to make them even better.

He found one of those people at age 10. Eighteen-year-old D’Andre Archie wasn’t just the coach of Bell’s basketball team. He was a father figure, a role that came naturally after he, too, grew up without a dad.

“I took it upon myself to be there, to be around — if he needed to talk for advice, if he wasn’t doing something right or if he was getting into it with his mom,” Archie said.

Archie is still that man today. He’s the first one Bell mentions as a father figure. Archie said the two have never had an argument, and Bell consistently comes to Archie for advice and stories of where life and basketball have taken him.

“He hasn’t always been the heralded guy,” Archie said. “He wasn’t always jumping over six people. He had to work hard.”

Archie has watched in real time Bell’s journey to beat the individual within. He watched it blossom in high school, where Bell first learned about transfer rules after moving from Serra High School in Gardena, Calif., to Pasadena High School.

Pasadena coach Tim Tucker said the individual shined immediately. Bell instantly became the best player on a team fresh off a state championship.

“He’s talented in the sense that he can walk into a room and do things that other players can’t do,” Tucker said. “He has that confidence about him that is amazing.”

At Pasadena, Bell’s wacky personality grew. Tucker remembers how he would roll up his shorts like old-school basketball players and sport the rimmed glasses NBA players now use as a fashion statement.

“Your personality doesn’t always dictate the way you play, and he shows up and plays,” Tucker said. “He loves the game. That’s the one thing I can say, is that he loves the game.”

But Bell wouldn’t always love the game.

—–

###“When pride rules on, promises don’t mean a thing” — Keion Bell’s “Loftly Wedded Warfare”

—–

When Bell signed on with local midmajor Pepperdine, he wanted to continue his success in the L.A. area and make his mark at a smaller program.

Bell scored more than 1,300 points in three years at Pepperdine, but he always felt like something huge was missing.

“I was an individual,” he said. “I had a lot of individual accolades. I wouldn’t even say success, I would call it a lot of individual accolades that I achieved at Pepperdine. It was nothing worth writing down, nothing worth talking about.”

Bell was again the best player on his team, but that didn’t equate to happiness when losses piled up and his goofy personality clashed with those around him.

“Any day you wake up and you dread being around the guys you have to work with every day, it’s just time to move on,” Bell said.

—–

###“Coach Haith is the professor, and he be teaching chemistry” — Keion Bell’s “Welcome to the Zou”

—–

When Bell visited Missouri as a potential alternative, coach Frank Haith said he arrived in a tough place. He was quiet and reserved, though in search of a support unit that would make him happy.

“If I was going to go back to school, I needed to make sure it was a perfect situation,” Bell said.

What he found were genuine coaches leading a team where the chemistry was “through the roof,” he said. Whereas some schools showed him that they wanted his services, Bell said Missouri showed that it needed him.

As soon as the visit to Missouri ended, Bell canceled his impending visit to Texas A&M. He called up Archie. He made plans to enroll.

He hoped the reassuring feeling of support would last. One day in the summer convinced him it would.

A Missouri player missed a summer school class, and the entire team had to run at 5 a.m. as a punishment. Bell expected to see upset players take out their frustration on the player at fault. He instead saw teammates lift that player’s spirits.

Bell said he saw that spirit consistently as he sat out the Tigers’ 30-5 season in 2011-2012. He bonded with fellow transfers Earnest Ross and Jabari Brown. He studied up on the leadership he saw from Kim English.

Bell said the chemistry goes right back to “the professor.” He labeled Haith as another father figure. He said Haith found him in a bad place and showed him a way out.

“Something I learned a long time ago is that you don’t coach basketball, you coach people,” Haith said. “You teach basketball. That word ‘coach’ is such a special word to me because that word ‘coach’ was my father figures when they were my mentors.”

Bell said he arrived at Missouri as an introvert but was immediately forced into a speaking role with the rest of the players. Haith said communication is one of his top teaching points because when players talk, that means they’re “giving to others.”

Haith said his goal was to teach Bell that the talents that made him special could make those around him better, too. Bell said he responded to Haith’s instruction to talk by using his personality to become a vocal leader in the locker room.

That genuine feel about Missouri that convinced him it was the place for him never went away, Bell said. He said each day feels just like that first visit with the support he receives from teammates and coaches.

“I can honestly say this is the first time I’ve seen him happy,” Archie said.

—–

It’s time.

He pulls the ball back with his right hand. Six people stand between him and the basket.

For a moment, nothing seems changed. The individual again.

He runs. He jumps. He slams.

The smoke pours. The crowd erupts. Every Missouri player runs after him.

And all of a sudden, everything has changed. Keion Bell has disappeared, the individual engulfed by the very teammates who have made him so much more.