Grant Elliott never quite knew what he wanted to do when he grew up, but he has always been a wanderer.

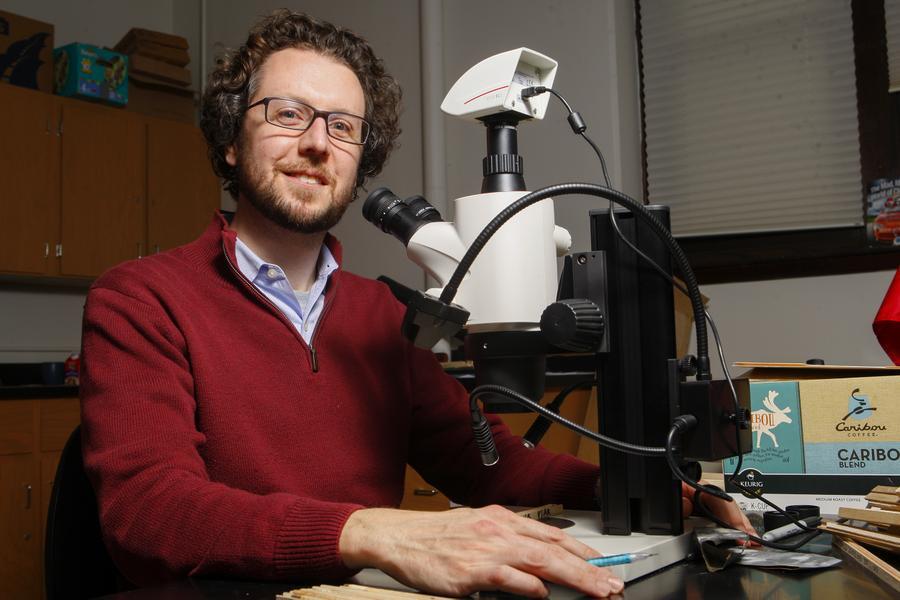

As an assistant professor of geography at MU, Elliott looks to the mountains to understand climate change. His work has led him to study how environmental changes affect the upper elevation limit of mountainous forests.

Elliott said a lot of factors affect tree growth — everything from changes in temperature to the side of the mountain the tree is growing on.

Getting to experience the expansive landscape of the mountainous forests is one of Elliott’s favorite job perks. He said people sometimes forget about the aesthetic value of a healthy environment when the climate gets brought up.

“When people talk about climate, that sometimes can get political,” Elliott said. “But when you go out and see these natural patterns and processes being impacted by changing climatic conditions, to me it’s one of the neatest things.”

Elliott’s love for nature and science began in childhood.

“(As a kid) I wandered around the woods a lot,” he said. “My parents would think I was kind of weird for wanting to hang out in the woods.”

When he started college at MU, Elliott said, he wasn’t very focused or attentive to his studies.

“I kind of feel like I understand students that don’t come to class often and are disinterested, because that was me for the first two years of my college career,” he said.

After doing poorly his first semester, Elliott decided to take classes he thought sounded interesting. One of those classes was a geography course, in which he learned that geography goes far beyond locating states and capitals.

After earning his bachelor’s degree in geography from MU, Elliott went on to earn his master’s from the University of Wyoming and his doctorate from the University of Minnesota-Twin Cities.

Evan Larson, now an assistant professor of geography at the University of Wisconsin-Platteville, worked with Elliott when both were doctoral candidates at Minnesota.

“Grant’s work really captures the essence of geography,” Larson said.

While in the field, Elliott studies climate change using a method called dendrochronology. He takes samples from trees and studies the rings. Changes in coloring or size in certain rings indicate how the climate around the tree was different during those years. For example, in years of drought the tree grows more slowly, causing a smaller ring.

In addition, Elliott measures how the outer limits of the forest are changing. As the climate changes, trees are able to grow at higher elevations. This means the forest has a larger habitat, but trees are encroaching on alpine environments.

Bradley Carlson, a Ph.D. candidate at the Laboratoire d’Ecologie Alpine in Grenoble, France, has worked on the same kind of research in the past, studying the Alps.

“You have the environment, which is sort of the contextual driver affecting treeline position,” Carlson said. “But you also have human land use, which shapes, to a huge degree, where the forest is right now and where it has been.”

Carlson is focused on studying the alpine and subalpine environments that forests are expanding into. While conservation of those habitats is an important part of his work, it is not the only reason the expanding forest is getting noticed. The portion of a mountain widely regarded as beautiful is usually the peak, or alpine portion.

“There is certainly an aesthetic consequence on the landscape,” Carlson said. “People tend to value an open mountain landscape where they have good views and they’re hiking above treeline. It’s a certain alpine experience that people seek.”

Elliott’s first experience with fieldwork was while he was a graduate student. He lived in the back of his truck for two months doing his research in the San Juan National Forest in Colorado. That year, there had been a drought and there was a forest fire in a nearby portion of the forest.

“The whole area smelled like a fireplace, and that was kind of my ‘trial by fire’ and introduction to fieldwork,” Elliott said. “I thought, ‘This is so cool. I can’t believe I’m getting paid to do this.’”

While having a fire as your next-door neighbor for two months may be interesting, it is not the only close encounter Elliott has experienced. He has weathered dangerous storms and has had several run-ins with wild animals throughout the course of his career.

“Grant had some amazing experiences in the field,” Larson said. “He had some incredible successes and some stories where you kind of scratch your head and wonder, ‘How in the world did all this happen?’”

Elliott said one of his most notable experiences to date involves a close encounter with lightning.

“I could hear the air sizzle,” he said.

He said the face of his friend on the backdrop of solid white lightning is etched into his mind. As they were running down the mountain away from the storm, Elliott slipped on some rocks and slid on a rock outcrop.

“Out of sheer terror, because lightning is crackling all around, I was like, ‘Man down! Man down!” Elliott said.

As if that was not enough, a ram blocked the path down the mountain. Elliott had to scare it out of the path without angering it, so they could continue running down the mountain to escape the storm.

Despite his close calls in the past, Elliott said he loves the forest. Now that he has kids, he hopes to share his love of the forest with his daughters. He even dreams of having a small one-room log cabin in the woods as a kind of hideaway one day.

Elliott never really stopped wandering, but now his forest has expanded in scope.

“When I was a kid, it seemed like a huge woods to wander around,” he said. “Now, it doesn’t seem big at all.”