Dr. Susanta Behura, an assistant research professor in the Division of Animal Sciences, has studied mosquitoes and their role in the spread of dengue fever for around seven years. Behura’s recent work has uncovered a connection between the genetic molecules of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes and the dengue virus.

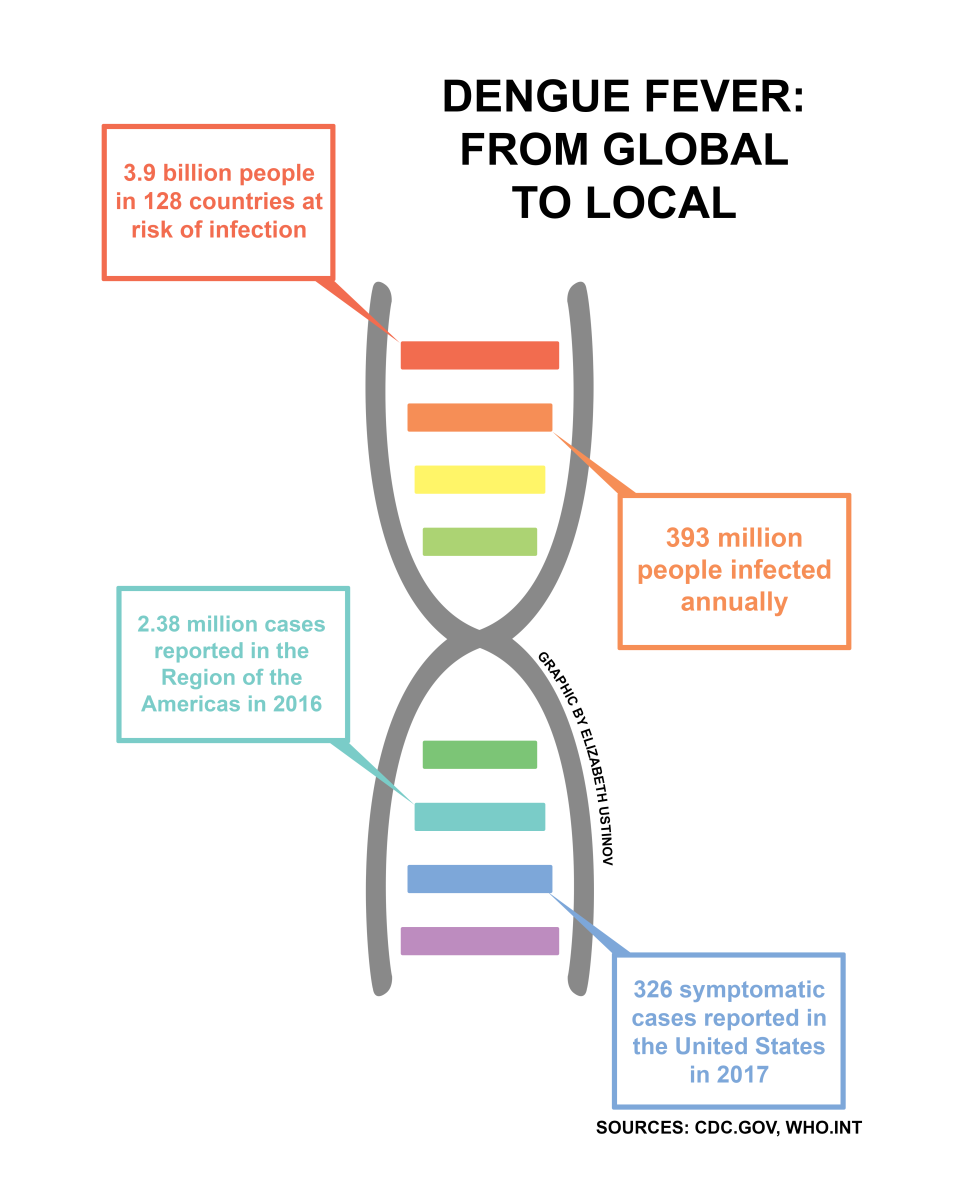

Dengue fever, a disease that resides mainly in tropical regions, is spread by Aedes aegypti mosquitoes and can emit joint pain throughout the body in addition to fever. It affects upward of 390 million people each year, Behura said.

Behura began his research in vector mosquitoes, those that spread disease from person to person, while working at the University of Notre Dame with professor David Severson.

Their findings have been published in the Public Library of Science’s Neglected Tropical Diseases journal and has led to the identification of a new class of small RNA molecules in the Aedes aegypti mosquito that is responsible for spreading the virus to humans.

“It’s exciting because this [research] provides clues that these molecules may play a role in transmission of the virus,” said Behura’s colleague at Notre Dame, Dr. Matthew Eng.

Eng said their research was conducted using colonies of mosquitos raised in an insectary that had experiments and analysis performed on them in a research laboratory at Notre Dame.

“We looked at a short type of short genetic molecule related to DNA called small RNA,” Eng said.

Very little is known about these RNA molecules in mosquitoes, but in other animals these molecules are vital to the regulation, expression and function of certain genes.

One of the goals of their study was to discover whether the level of small RNAs was different between mosquitoes that were vulnerable to carrying dengue and mosquitoes that were resistant, Eng said.

“Interestingly, we found that some of these small RNAs were increased in the resistant strain only when they were fed blood with dengue virus,” Eng said. “It’s exciting because this provides clues that these molecules may play a role in transmission of the virus.”

There are methods to protect from mosquito bites during the night, such as mosquito netting, but the Aedes aegypti mosquito attacks during the daytime, which proves to be more difficult to prevent bites, Behura said.

“There is literally nothing you can do to protect yourself from this mosquito,” Behura said.

Because of the lack of prevention methods, time of day bites occur and limited resources, dengue fever affects large populations in the tropical regions it is present.

Behura has had personal experiences with dengue fever, as many of his friends and family live in India, where he is from.

“I have seen a lot of my friends and relatives hospitalized because of this infection,” Behura said. “Some have almost died from it.”

Behura said dengue fever is a “neglected disease which is a growing problem.”

The mosquitos breed in small, swampy areas, which can be devastating to the populations of people near them. The summer and rainy seasons also influence mosquito breeding.

Dengue fever has also shown prevalence in the United States, especially in parts of Florida and Texas. When travelers visit from countries where dengue fever is common, they can pass on the disease.

“We are not at risk in the U.S. yet, but we should definitely continue survey of mosquito populations that may cause local transmission of the virus in small pockets,” Behura said.

Typically, it takes seven to eight days for the symptoms of dengue fever to take effect.

Children are more at risk to exhibit severe symptoms because they have weaker immune systems. Behura said more than 20,000 children die every year from dengue infection.

Currently, there are no existing vaccinations or treatments for dengue fever.

Behura and his colleagues have plans to use genetic molecules of the mosquitos and the receptors in the mosquito that transmit the disease to prevent its spread.

“One way to control the disease is to make the mosquitoes incapable of spreading the virus,” Behura said.

Severson has collaborated with Behura on the research involving the mosquitoes and dengue fever and has traveled to multiple locations around the world to gain first-hand experience and knowledge.

Severson was among the first to develop genetic linkage maps for mosquitoes using DNA-based markers and led the initial Aedes aegypti genome sequencing project.

“It was amazing to me, as it allowed us to see how particular cellular pathways [in the genome] respond to the virus, and these results have given us ideas for new studies, always with the goal of eventually identifying new disease control methods,” Severson said.

Behura said the way to prevention is to focus on the female mosquitoes because they are the sole perpetrators when it comes to spreading dengue fever. Male mosquitoes only go from flower to flower to collect nectar, but females need human blood to maintain the ability to reproduce.

“We know a lot about how dengue fever is transmitted from mosquito to human but we still do not have the power to control the disease,” Behura said. “This is a big problem, but we should not give up. We are working really hard to come up with a solution that might, one day, eradicate this problem.”

_Edited by Morgan Smith | [email protected]_