Stephanie Logan was 23 years old when she lost her hearing.

It was unexpected— Logan, who had complete hearing up to that moment, had contracted bacterial meningitis. A combination of the medication and high fever caused complete hearing loss. They say the best way to learn a language is through immersion- for Logan, deafness and American Sign Language had become her country.

“I had studied German, French, Spanish,” Logan said. “I loved languages. But I would’ve never learned American Sign Language. It was not in my personality. Sign language is so visual, a lot of moving your body and I was pretty reserved.”

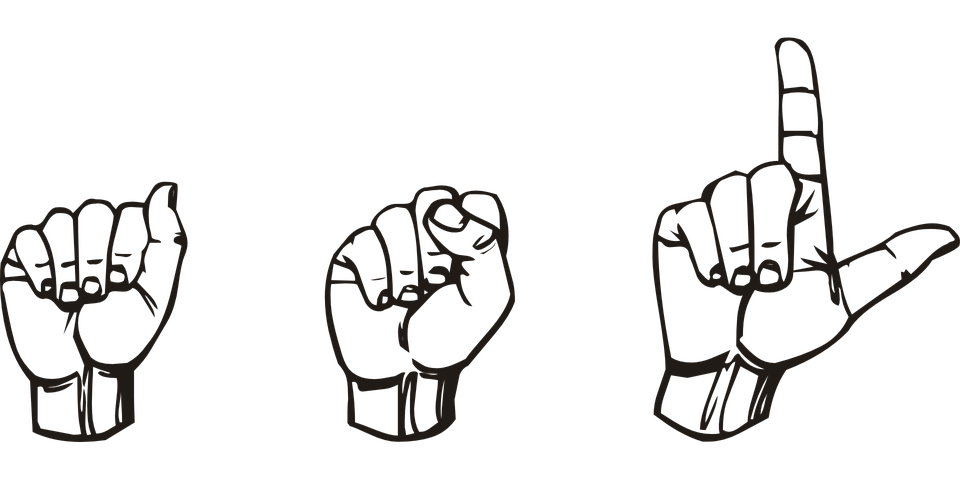

ASL is 90 to 95 percent body language and facial expression and 5 to 10 percent the actual signs.

“What a Deaf person is expressing visually in ASL is similar to how hearing individuals express themselves with their intonation,” she said.

Now, Logan is helping others learn the language that has become a vital part of her life. After learning ASL at Gallaudet University in Washington, D.C., she finished her education at her original college, the University of Georgia, with the help of an interpreter. Speech therapy helped her regain the ability to speak and now, her fluency in both English and ASL allows her to bridge the gap with those who’d like to learn ASL.

Logan has worked as the executive director of DeafLEAD, a non profit agency whose purpose is to provide 24 hour crisis intervention, advocacy, interpreting and mental health services to deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals, for 23 years.

She offers five eight-week ASL classes every year, which are open to anyone interested in learning.

“Since the beginning of time, [the classes] have been $100, I’ve never really changed the rate,” Logan said. “They meet once a week, I have Tuesday and Thursday beginner classes and people are able to interchange those classes.”

The beginner classes meet from 5:45 p.m. to 7 p.m and the intermediate/advanced class meets Thursdays from 7:15 p.m. to 8:30 p.m.

Additionally, Logan teaches as an ASL professor at MU, but her community classes offer a much cheaper introduction into the language. The community classes are also lower stakes- Logan teaches in both ASL and English, in order to ease any anxiety her students may have about learning such a extroverted language.

“If someone takes my beginning class and they have no sign language experience, I recommend they take the beginning class two times, because it helps them get a real foundation for the signs they learn in that class,” Logan said. “After two times, they have to go to the next class. I have folks all the time that start out in my eight week class, then take my university class because they figure out they have a real interest in the language.”

People from all walks of life come to DeafLEAD to learn ASL. Motivations vary, as do prior skill levels.

“I am the property manager of the apartment community [by the DeafLEAD office],” Camaron Nielsen, one of Logan’s advanced students said. “One of my residents moved over here from Ethiopia with his family. He is a deaf individual, but he didn’t have any language, spoken or signed language, nothing.”

Despite not knowing any formal language, Nielsen said he was one of the best communicators she’d ever met.

“He started coming here and taking classes at DeafLEAD and actually learning ASL,” Nielsen continued. “It was very cool to see the way his face would light up being able to sign and really communicate with people in a way that he hadn’t before. I started taking classes here to be able to better communicate with him.”

The classes are also useful as refresher courses for individuals who are already familiar with the language. Logan said that for some people, it becomes like a book club, something they do to keep their toes in the water and their signing skills up.

“My college roommate’s best friend was deaf, so she was always over signing. She had a cochlear implant, so I could talk to her and she could read lips, but it was helpful when I knew how to sign back to her, so I learned a lot from her,” advanced student Ashleigh Herrin said. “I graduated two years ago, and it’s been a while so I just wanted to get back into it. These community classes are super helpful.”

Logan uses a variety of activities to keep the classes new and interesting. One of these activities is tactile signing, the method used to communicate with deaf-blind individuals.

“It’s a very unique experience,” advanced student James Cutts said. “The way we’ve done it, one person is a deaf-blind individual, and the other is signing. The deaf-blind individual is either blindfolded or keeps their eyes closed.”

ASL in general is much more physical than spoken language, but advanced student Cynthia Fennewald said tactile signing requires crossing touch boundaries that are very firm in American culture.

“It’s unexpectedly intimate, because you’re touching the person’s hands for an extended period of time,” Cutts said. “It is very challenging, and makes me feel as though I’m just starting to learn ASL from the ground up every time we do it. I know a couple people who are deaf-blind, and it’s interesting to practice with them, but also as a practice in empathy, because for them, this isn’t just an exercise they do every once in a while. It’s what every day is like for them.”

_Edited by Morgan Smith | [email protected]_