Ezra Bitterman is a freshman journalism major at MU. He is an opinion columnist who writes about elections and societal observations for The Maneater.

In President Dwight Eisenhower’s final address, he left the country with a fateful warning about the power of the military-industrial complex.

“In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex … the potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.”

Eisenhower, as a military man himself, foresaw how the military could harmfully extend its influence into other areas of American life. The military has quietly, yet effectively, infected the film industry. Taking creative control over film in exchange for unparalleled access to military life, Hollywood and the Department of Defense have created a propaganda machine.

The DOD has had a hand in Hollywood for years, starting with “Wings,” winner of the first Academy Award for Best Picture. Yet DOD meddling has gained prevalence with modern movies like “Iron Man” and “Zero Dark Thirty.”

The DOD offers a simple yet attractive offer to film producers. The DOD retains ultimate control on the script, production and final product; the filmmaker gets military guidance for accuracy, access to personnel and can use available equipment.

These arrangements produce movies closer to strategic communication than anything creative. When the military gets flack for using torture, they can make a movie justifying it– thus allowing injustices to continue.

As a basic rule, government institutions should not be able to sway the creative process. Their priorities are not in creating something honest for the public, but something displaying them in the best possible light. In an advertisement, it’s reasonable to expect that the advertiser is going to present themselves the best they can, so consumers take everything with a grain of salt. When watching a film, consumers expect to be entertained, so they let their guard down and are susceptible to subliminal manipulation.

Unfortunately, the relationship between film and the armed services today isn’t unique. Going back to the Soviet Union after World War II, a similar trend happened in their film community. Filmmakers in the shadow of the war were hesitant to criticize the Soviet state even after communist leader Joseph Stalin’s death. Andrei Tarkovsky — maybe the greatest filmmaker of all time — broke that trend with “Ivan’s Childhood.” It’s about a Russian boy whose family is killed by the Nazis; he dies in battle trying to avenge them.

Tarkovsky, making the movie from personal experience, strived for honesty in the story. While the movie may unsettle viewers, its key thesis is something missing in today’s entertainment output: Even in victory, war has no winner. It’s harmful for the military to come off as entertaining because even when acting nobly, people still suffer. The film industry allows armed services to be portrayed as heroic freedom fighters, giving way to a false sense of confidence in the military solution.

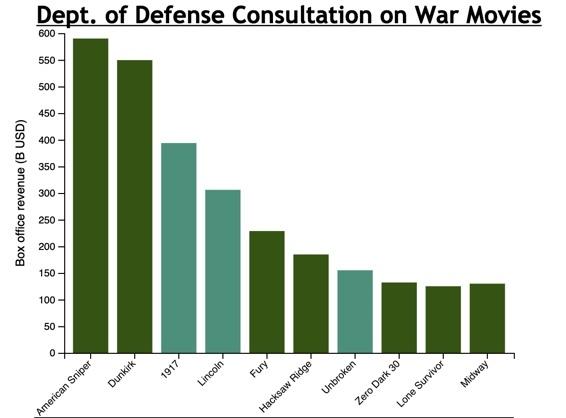

Unfortunately, Tarkovsky could not make the same cultural impact in today’s Hollywood landscape. Big budget war movies —”Zero Dark Thirty,” and “American Sniper” are some examples — suck up consumer attention so that smaller-budget movies portraying the military more evenly can’t have a similar impact.

Ridding Hollywood of military interference wouldn’t suddenly level spending across all movies. However, it would sway producers from dishonest storytelling. A movie critical of the armed forces might get more financial backing and thus a larger audience.

In addition, without Pentagon interference, up-and-coming writers would feel more empowered to display the military however they like — without fear of getting no support. Finally, it’s important to understand that film is a game of compromise. To produce something, creatives often have to give up some of their vision in the name of practicality. The military should not be that sacrifice; filmmakers should not have to give up their vision to make a government institution happy.

As military recruitment stagnates in the 21st century, the institution has backed other movie genres, namely sci-fi. Unlike gory military dramas appealing to the early-20s male crowd, “Iron Man” appeals to kids. The military hopes that the younger generation associates the military more with the heroism of Avenger Tony Stark than the Guantanamo Bay detention camp.

All in all, having two major genres in Hollywood under the thumb of a government institution extends the reach of their power, allowing them to control the narrative of their actions, not the people affected by them.

Movies are not documentaries — they don’t need to be 100% accurate. As a creator, it’s essential to have some idea of the consequences of what you’re putting out there. I love film, and to see it morph from a place of expression to one of salesmanship hurts my heart. It’s time to kick the military out for the sake of our country and the film industry.

The International Rescue Committee is committed to helping the people of Afghanistan.

Edited by Sarah Rubinsten, [email protected]