TW: This article contains mentions of war, slavery, segregation and Neo-Confederatism.

Inside The Broadway Hotel’s Katy Ballroom on Saturday, three writers discussed their experiences with an emotion that could have gotten them publicly ridiculed just a few hundred years ago.

Once considered a psychopathological illness, nostalgia — a deep yearning for the past — was the centerpiece of “Those Were the Days,” a panel at the 2022 Unbound Book Festival. This year’s festival welcomed back in-person attendees for the first time since 2019.

International Book Awards Finalist Donald Quist moderated the panel, which featured essayist David Berry, poet Caki Wilkinson and novelist Eric Nguyen as they unpacked nostalgia’s unique role in literature and daily life. The panel’s in-depth look at this complex topic made it clear that true nostalgia is far from the illness it was once presumed to be. Instead, nostalgia is a commonplace way for humans to cope with the passage of time.

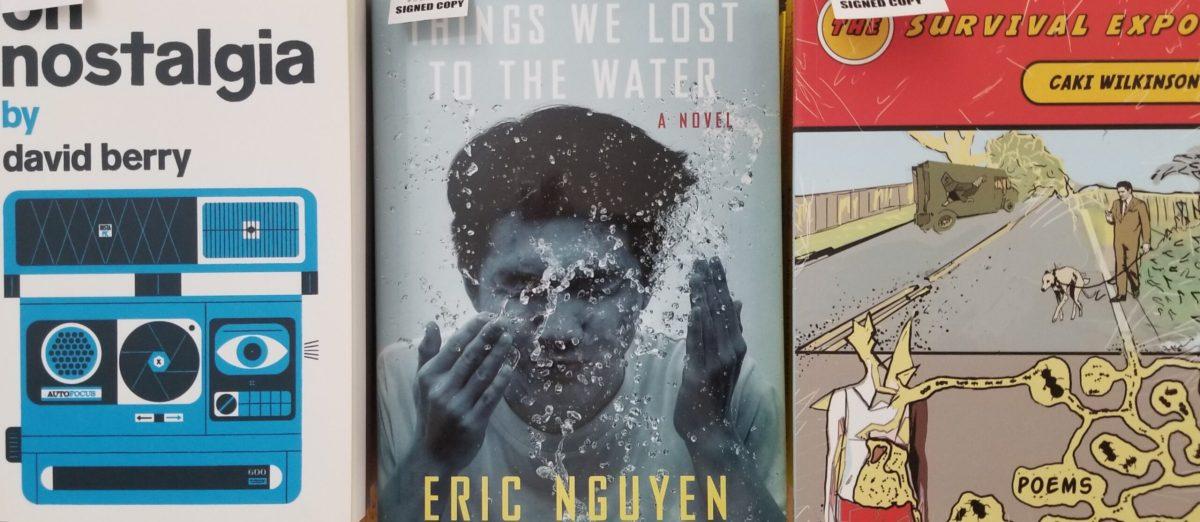

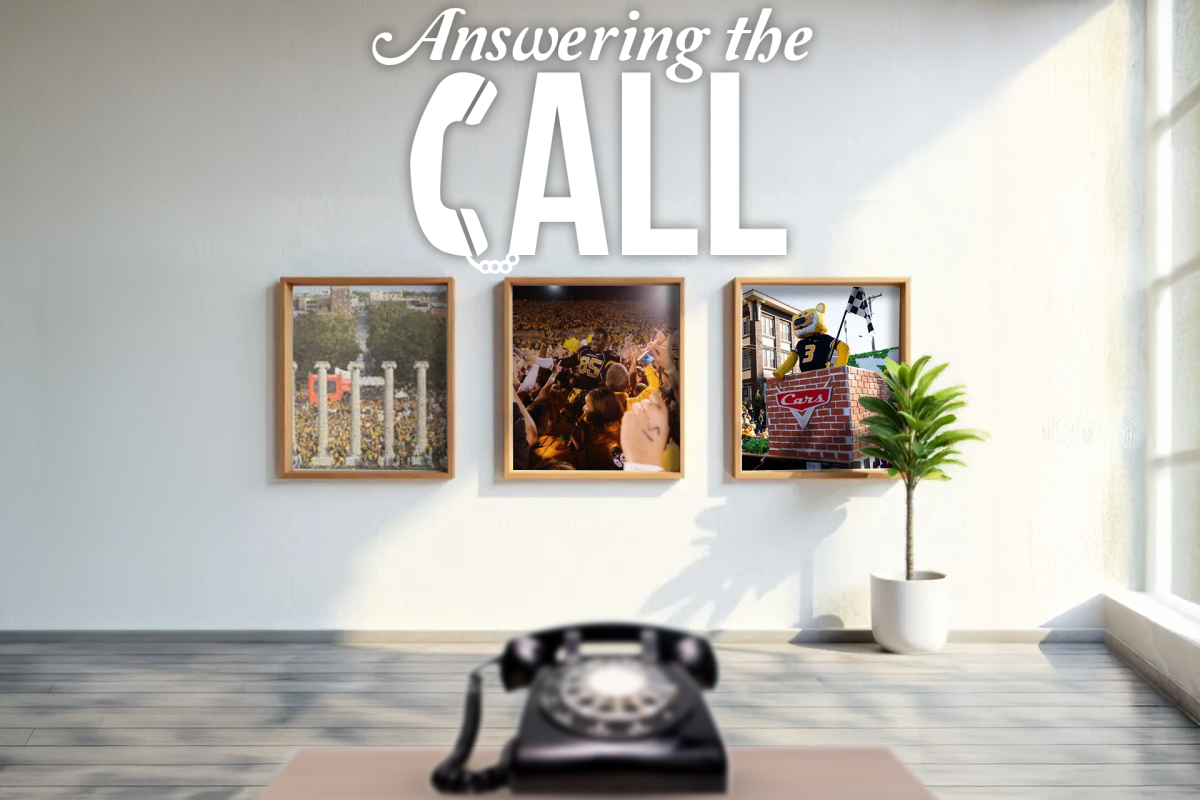

Each author enriched the panel with pieces of their own written work. Berry read aloud from his book, “On Nostalgia,” Wilkinson recited some of her poems from “The Survival Expo” and Nguyen read an excerpt from his first novel, “Things We Lost to the Water.”

“Things We Lost to the Water” follows a Vietnamese family as they move to the United States in the wake of war, grappling with poverty, loss, self-discovery and nostalgia’s omnipresence in their lives. Nguyen read a passage that depicted Hương, one of his novel’s main characters, tasting a longan fruit and remembering what life used to be like back in Vietnam.

“Hương held it gently and bit into it slowly, wanting the flavor to last, wanting to picture herself in an orchard, so very much like this one, on the outskirts of Mỹ Tho,” Nguyen read.

Nguyen’s words are a stirring reminder that nostalgia’s love of “the good old days” sometimes implies the rise of dark times between the idyllic past and the uncertain present. For Hương, yearning for the past means longing for, as Nguyen writes, “a time that was simpler, before war, before marriage, before the fall of a country….”

One of Wilkinson’s featured poems transported the audience to Elvis Week, a celebration of late rock ‘n’ roll artist Elvis Presley, in Memphis, Tennessee.

Wilkinson’s written portrait of the bustling streets of Graceland, the sweltering August heat and the charismatic Elvis impersonators, both “old and not so old,” swells with nostalgic undertones. Here, nostalgia for a long-gone celebrity and his music is not just an individual experience, but a collective sentiment.

Berry’s essay excerpt captured nostalgia’s unpredictable nature. Whether or not we expect certain snapshots of our lives to become nostalgic is ultimately irrelevant, since so much of “what is, is rather rapidly becoming what was.”

Likewise, the notion that the present can only be fully lived in once is a somber one, and such “anticipatory nostalgia” may influence our enjoyment of precious moments — even as they’re just beginning to unfold before us. Still, Berry said he does not wish to vilify nostalgia.

“Bittersweetness is what nostalgia is about,” Berry said. “How can you go through life and not ever want something back?”

After the authors showcased their writings on nostalgia, Quist asked them to share their perspectives on nostalgia’s political pitfalls and its restorative potential.

Berry mentioned how political rhetoric can tap into an electorate’s collective nostalgia, with language ranging from the Trumpian call for reinvigorated American exceptionalism, “Make America Great Again,” to the “Green New Deal,” a reference to the New Deal of the 1930s.

However, Berry noted that nostalgia’s presence in politics may jeopardize the rights of people who weren’t represented in political life until much more recently.

“When you are harkening back to some golden age, you are almost explicitly creating an ‘other’ who wasn’t a part of that,” Berry said.

Wilkinson added that she hails from the South, a region that continues to grapple with its distinct legacy of slavery, segregation and Neo-Confederatism. She then emphasized nostalgia’s complicated relationship with such a legacy.

“Nostalgia and nostalgic versions of the South — they’re everywhere,” Wilkinson said. “[For example], you can go get married on a plantation in Louisiana … That is something that I think is, for a lot of Southerners, a source of shame … There’s an interesting way that shame and nostalgia are kind of feelings that are going in different directions.”

As for nostalgia’s restorative qualities, Nguyen brought to light nostalgia’s power to help people move forward, especially communities impacted by common hardships. Nguyen referenced his fictional Vietnamese characters from “Things We Lost to the Water,” as well as the hundreds of thousands of real Vietnamese people who were displaced by war in the late 1970s.

“I think nostalgia really helps in building a community [of] people who were displaced,” Nguyen said. “[They] have the same kind of [cultural] memory.”

By the end of the panel, perhaps more questions were raised than answered about our human desire to relive the past. However, the three authors made it known that nostalgia — a beautiful heartache of an emotion — permeates the pages we read and the memories we cherish.

“The chief … benefit of nostalgia is that it gives us this sense of self or maybe, more importantly, it’s sort of a reminder of what we wanted to be,” Berry said. “It’s basically an identity-maker.”

David Berry, essayist

Edited by Lucy Valeski, [email protected]