“Karen” is popular slang term for a woman who is entitled, demanding and obnoxious. You know her from videos on the internet of her demanding to speak to the manager over minor non-inconveniences or calling the police on innocent people.

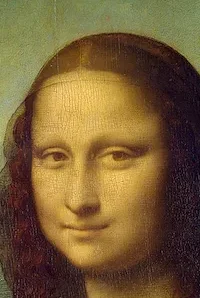

And the “Mona Lisa” is, well, the “Mona Lisa.” Painted in the High Renaissance by Leonardo da Vinci, it is one of the most famous paintings in the world.

I shall now take you through a journey of why “Mona Lisa” is a Renaissance “Karen.” It makes perfect sense; that is, if you read just a little too much into the artwork.

Let’s first look at the person behind the smile. The model for “Mona Lisa” is believed to be Lisa del Giocondo, the wife of a wealthy silk merchant from Florence, Italy. Being a merchant’s wife, “Mona Lisa” can be interpreted as a symbol of consumption. This is further heightened by her extensive copying and reproduction in popular culture, where she is translated into any imaginable product (think shirts, postcards, rubber ducks, Andy Warhol works and infinitely more examples.) In this way, she holds an interesting duality relating to consumer culture. She is both in a position of power and agency — on the production side — but at the same time, she is an object of production. She is able to wield power, yet power is still wielded over her.

The “Karen” holds this same duality. She is economically powerful and has purchasing power. At the same time, the “Karen” has evolved in a time characterized by the loss of consumer agency as a result of the overproduction, effectivizing and automatizing of most industries. In other words, because of the way production works nowadays, the customer is no longer always right. This lack of agency frustrates the “Karen,” and she feels at a loss of power. She desperately tries to hold on to her power, and this is why she demands to speak to the manager.

Zooming in on the painting, we see how the “Mona Lisa” has her right hand resting on her left. This is a symbol in Renaissance art of a virtuous woman and a faithful wife — kind of like a wedding ring. Virtue in Renaissance art is heavily reliant on the defining saying of the time: “Virtutem Forma Decorat,” which means “virtue adorns beauty.” This means that virtue is the highest of a woman’s, well, virtues, and it shows beauty is found in the things we do and not how we look.

Being virtuous is one of the most important traits of a “Karen.” The “Karen” calls for institutional protection of her virtues — some examples of virtues to be protected are her “right” to not be offended and demanding that others follow her personal moral compass. This is because it upholds a system that gives her certain privileges she is afraid of losing. We see this in her entitlement — she tries to demand a lot of things and expects the world to give in.

Both “Mona Lisa” and “Karen” try to show off their virtues to the world, whether through folded hands or a lavish appearance that shows they have more stuff than you. The ladies feel defined by the virtues they show off that offer a sense of security for them, whether false or true.

Lastly, let’s return to that mysterious smile. The smile has an effect that makes it hard to decipher if the “Mona Lisa” is smiling or not. From certain angles, she is indeed smiling. From others, she is not. This is due to a certain technique called “sfumato” which employs soft, smoky transitions between colors in the painting process. This technique shows off da Vinci’s incredible skills, as he managed to create an optical illusion around the mouth using color and shading. But enough about painting techniques — the meaning of an illusionary smile is linked to the “Karen” in more ways than the fact it is painted on.

When you see “Mona Lisa” from the side or from a distance, she is smiling. In the same way, when you initially see a “Karen,” she may just seem like another neighborhood soccer-mom with an unfortunate haircut. But once you stand face to face with a “Karen,” she is no longer nice. Rather, she will call the police on you and harass you to get her way. And that smile of hers that you took for a good thing turned out to be superficial — and mysteriously able to change just by getting on her wrong side.

So there you have it. The Renaissance “Mona Lisa” and the modern-day “Karen” have a semi-disconcerting amount of common traits. Use that information for what you will.

Edited by Ever Cole | [email protected]

Copy Chief — Jacob Richey | [email protected]