February marks the start of Black History Month, a national tradition tracing back to 1926. Read about the first moments in Black history at MU, from the struggle to desegregate MU to the first Black member of the Board of Curators.

Black History Month celebrates the Black community, its culture and achievements while honoring the Black struggle for freedom and justice in the United States. Here is a brief history of the month’s origin and the actions toward equality made by Black students at MU.

In 1915, renowned historian and civil rights activist Carter G. Woodson and American minister Jesse E. Moorland founded the group now known as the Association for the Study of African American Life and History. Through the creation of ASALH, Woodson and Moorland aimed to bring attention to and uplift the historic achievements of Black Americans.

In 1926, the ASALH sponsored the first national “Negro History Week” during the second week of February, as a nod to honor the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass. However, Woodson hoped to broaden the scope of the week’s attention beyond merely Lincoln and Douglass to facilitate discussion of African American history at large.

This week-long celebration eventually evolved into informal Black History Month celebrations on many college campuses, most notably at Kent State University in 1970. In 1976, President Gerald Ford officially recognized Black History Month.

Later, in 1986, the U.S. Congress passed a joint resolution, federally designating February as National Black History Month. In a presidential proclamation, President Ronald Reagan identified the formal purpose of the month as making, ”all Americans aware of this struggle for freedom and equal opportunity.”

Each February, every U.S. president has continued recognizing Black History Month, as well as a yearly theme ASALH establishes.

The 2023 theme is “Black Resistance,” honoring the vast history of Black resistance against oppression in many forms, including an ongoing fight for voting rights and education, according to the ASALH website. ASALH describes this year’s theme as “a call to everyone, inside and outside the academy, to study the history of Black Americans’ responses to establish safe spaces, where Black life can be sustained, fortified, and respected.”

Early Black History at MU

The struggle to desegregate Missouri schools was characterized most clearly at MU, as outlined in several articles and materials within JSTOR Daily and the JSTOR Library.

In 1936, Lloyd Gaines filed a lawsuit against MU after he was denied admission to the School of Law. Gaines was a student of Lincoln University, a historically black institution, which did not offer a law program. His petition garnered support from the NAACP and was heard by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1938. The Supreme Court ruled that MU violated Gaines’ 14th Amendment rights and declared that the university must either integrate or Missouri must provide funding to Lincoln University for a law school to uphold the “separate but equal” state mandate.

The Missouri Supreme Court later ruled against integration and instead designated $200,000 to build a law school at Lincoln. Lincoln used the funds instead to strengthen its undergraduate programs, keeping MU in violation of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling and holding the door open for continued legal action.

The struggle for desegregation and admission to MU was taken up by several students after Gaines, most notably in pursuit of a journalism degree. Lucile Bluford took a similar legal route to Gaines, and rather than admit a Black student to MU, the state afforded Lincoln $60,000 dollars for the creation of a journalism program.

In 1944, Edith Louise Massey, despite her admittance to the Missouri undergraduate journalism program, was barred from receiving instruction on campus as MU faculty maintained segregation practices by traveling to Jefferson City to teach journalism courses at Lincoln.

The Gaines/Oldham Black Culture Center, named in part after Lloyd Gaines, was established in 1972, originally known as the Black Culture House. It was founded in response to demands from the Legion of Black Collegians. One student at the time saw the center as a “matter of survival,” according to reporting from an April 4, 1972, edition of The Maneater. The center keeps a “Notable Firsts” page on its website where it documents achievements by Black MU students, many of which are highlighted below.

Following a court ruling in 1950 that desegregated MU, Gus T. Ridgel was one of nine Black students to enroll at MU, even as segregation remained legal until the 1954 Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education. Ridgel went on to become the first Black graduate student and received his Master of Economics in 1951.

In 1956, Al Abrams Jr. became the first Black person to accept an athletic scholarship to play at Missouri. Abrams played with Missouri men’s basketball from 1958-1960 and was inducted into the MU Hall of Fame in 2004.

The Legion of Black Collegians was founded in the fall of 1968 by charter members of the Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity’s Zeta Alpha chapter in coordination with Michael Middleton, a current MU deputy chancellor emeritus and professor emeritus of law. LBC remains the only recognized Black student government in the U.S.

In 1971, Theodore D. McNeal took office on the Board of Curators, becoming the first Black member to serve as a Curator. McNeal was appointed by the Missouri governor and “felt honored” to receive the position, according to a Jan. 8, 1971, edition of The Maneater. McNeal was also the first Black Missouri state senator.

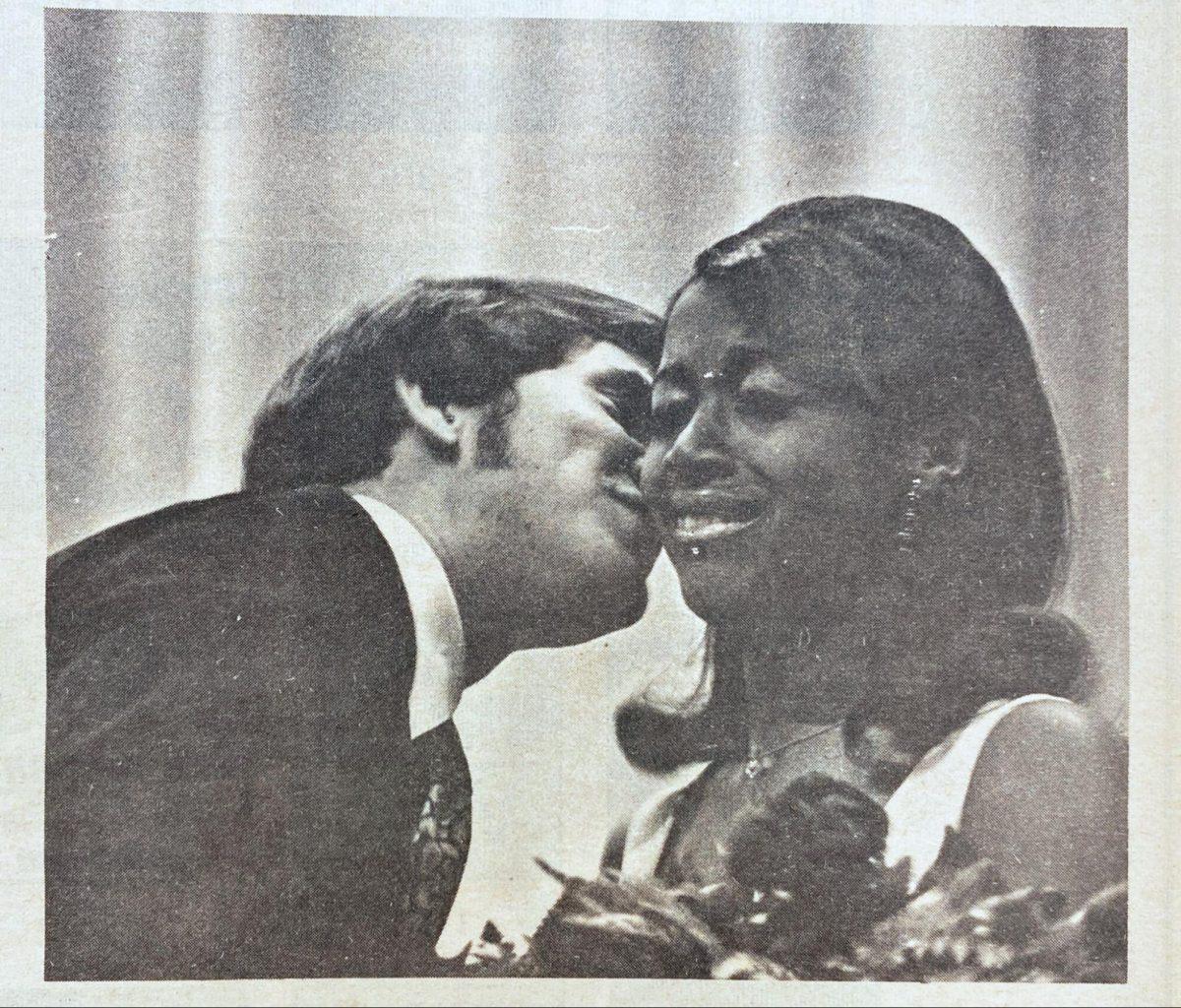

Later in 1971, Jill Young became the first Black woman crowned Homecoming Queen at MU. In 1984, Anthony Wilson became the first Black man crowned Homecoming King, according to the center’s website.

“It took more than Black votes alone,” Young said after hearing she won the title, according to an Oct. 27, 1971, edition of The Maneater. “I believe I was selected to represent the students by the students.”

Dr. Marian O’Fallon Oldham, was appointed as the first Black woman curator in March 1977 by Governor Joseph Teasdale. Oldham was also refused undergraduate admission to MU based on her race, but went on to become a St. Louis school teacher, civil rights activist and was reappointed to her position on the University of Missouri Board of Curators in 1979.

The achievements of these individuals merely scratch the surface of the histories and successes of Black students, faculty and administration at MU. Beyond the 1970s, the struggle for true equality within the university for Black students persists. The Maneater will continue to outline examples of Black resistance, excellence and history throughout the month of February and beyond.

Edited by Zoe Homan | [email protected]

Copy edited by Mary Philip