The second short documentary collection of this year’s True/False Film Fest, “Shorts: Winter,” showcases conflict and survival in unique and stunning ways

True/False Film Fest’s second Shorts collection to screen, “Shorts: Winter,” opens with a minute-long film of two boys playing rock, paper, scissors. This foreshadows the conflict to come in the five films that make up the collection. Through this conflict, the audience sees remarkable stories of survival in harsh worlds.

The first film, “Lanawaru,” (meaning “grandfather caiman”) centers around a boy named Moises in Puerto Caimán, who must travel on the Rio Caquetá often. The audience immediately sees the danger of this as a man announces on a small radio that one of the men in his group did not return from their trip out.

Moises talks to his grandfather about his fear of traveling on the water. He tells him about a time when his and his uncle’s canoe had been overturned on the river, and he had seen the giant face of a caiman, a Central and South American reptile. His grandfather encourages him as he performs a protection ritual on Moises to aid his fears.

The film’s connection with nature is apparent. On the water, viewers see Moises through his reflection. Outside, they hear the sounds of birds and bugs in the Amazon. Though apprehensive about the dangers of nature, Moises seems to have a deep connection to it.

Director Angello Faccini presents the audience with a story less about the dangers Moises faces working near his maloca, but about the bravery he shows and the love his family and community have for him.

The next film, “Guardian of the Well” opens with expansive shots of a green desert. “This used to be a big town,” said a man, stopped at a well. “But then all the livestock died.”

Throughout the film, directors Tahir Mahamat Zene and Bentley Brown show a town affected by historic drought and flood, one after the other. Several grass homes in the town have been taken down and fed to the remaining cattle which also grow fewer and fewer each day.

The man at the well has no cattle now, saying he is “living off God’s grace now.” The camerawork shows the incredible conflict between nature and man, drought and flood, and hope and despair all while a heavy cloth full of water is pulled out of a well, the pulley rhythmically and abrasively thumping.

Though the shortest of the collection, “Guardian of the Well” gives viewers a good look at a community affected by nature working to survive.

Throughout the films in “Shorts: Winter,” impressive attention is given to sound. In “Animal Eye,” the sound design puts the audience in a philosophically focused optometrists lab, where the audience follows scientists using machines to understand how animals see the world by using cameras to look through their physical eyes. Whether it be through the crawling of a baby octopus or the squelching of a removed fish eye.

The visuals are psychedelic. The audience gets to look at a researcher through the physical eye of a fish as he works. His end goal is to have a camera look through the eye of the fish, in order to understand the world through a different lens. The documentary is made on expired physical film, giving it an old and unique quality.

At one point, director Carlo Nasisse models a purple and pink forest through static. The audience watches it rise and shrink as it changes color and resolution all while a researcher explains that what humans see isn’t the full objective reality. As a study of vision, the film is visually exciting and deeply philosophical.

“No se ve desde acá (You Can’t See It From Here),” shows a dizzyingly luxurious Miami condominium complex called the Missoni Baia, where each condominium goes for millions. Viewers quickly learn that a number of these condominiums stay empty for large portions of the year. In fact, for most of the residents, it is their second or third home.

Some of these residents come from South America, and through purchasing a condominium, they have an easier time getting a green card. For these wealthy immigrants, owning a condominium at Missoni Baia signals a movement in their capital from places like Colombia.

The audience sees the luxurious properties juxtaposed against a charitable organization called San Vicente, which helps people who have recently entered the United States get on their feet if they are struggling. This contrast serves as a stark reminder of wealth inequality in the immigration process.

The film then pivots into the experience immigrants have learning about America. The film, however, seems to get lost. Director Enrique Pedraza-Botero adds frenetic strobe-like editing and clips of speeches, media and footage all related tangentially to the concept of the “American dream.” In one scene, footage of an American plane dropping bombs plays. In another, employees work on a shipping dock while an unknown woman expresses anti-immigrant sentiments.

Overall, the film may have had too wide a scope for its short runtime of 19 minutes. While the themes of immigration and capitalism guide the film, they cause others, like the wealth inequality symbolized by the Missoni Baia, to lose some of their impact as the film moves on to issues like xenophobia and American militarism.

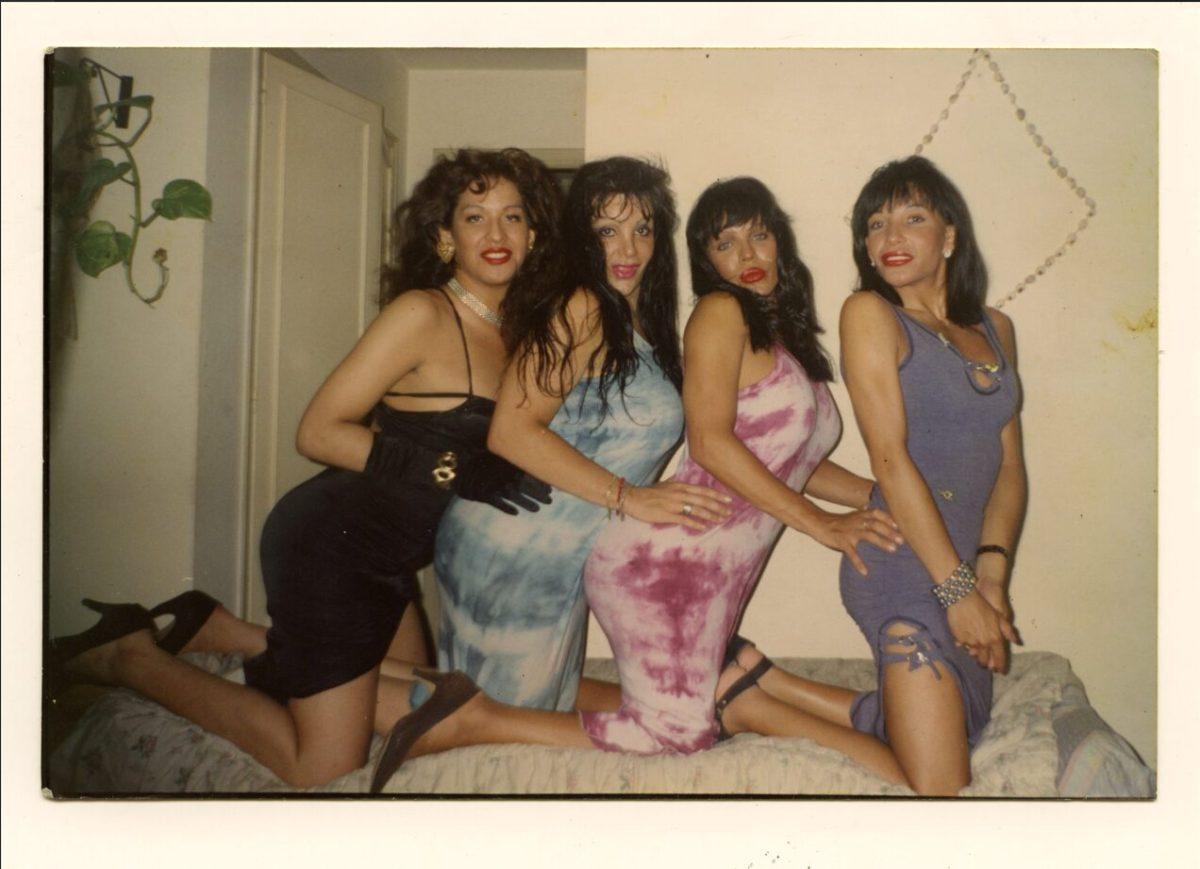

The final film, “Razeh-del,” takes the audience to Iran in 1998. Two women, one identified as Roya and one unidentified, decide to make an “impossible film” that the Iranian Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance would never approve for distribution. Their story is intertwined with the story of Zan, a newspaper which focused on the rights of women in Iran.

Director Maryam Tafakory tells the story mainly through superimposed text shown beneath abstract visuals and clips of women from 1990s Iranian movies. Most of the story is read like a diary from the perspective of the unidentified woman. The women write letters to Zan repeatedly, asking for their script to be published, but it never is.

Tafakory reveals that Zan was forcibly shut down. The two women writing to the newspaper get into trouble with authorities and their families when one of their letters to Zan that included a film demo is found. The end is heartbreaking but is set up as an inevitability throughout the film.

In “Razeh-del,” the audience sees the perseverance of two women working to create their film in a culture that was not willing to accept it. While the composition of the documentary is unique, it doesn’t detract from the overall story and instead grounds the narrative as something that has happened squarely in the past. The audience mourns for a film that never was completed.

The characters and their defiance of the laws and the Iranian Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance are inspiring. The film does not stay in despair but shows people who are remarkably strong and brave.

Throughout “Shorts: Winter,” the world shown through these short documentaries may be seen as harsh or bleak. But, as “Animal Eye” reminds us, there is more to the world than the audience can see. Throughout the collection, viewers are presented with stories of as much survival and hope as conflict and pain.

“Shorts: Winter” will be showing again at 6 p.m. on Sunday, March 2, as a part of True/False Film Fest at Rhynsburger Theatre in downtown Columbia.

You can keep up with The Maneater’s 2025 True/False Film Fest coverage here.

Edited by Alyssa Royston | [email protected]

Copy edited by Natalie Kientzy | [email protected]

Edited by Emilia Hansen | [email protected]

Edited by Annie Goodykoontz | [email protected]