Artist Lauren Frances Evans sculpted a vision of reclaiming virginity, birth and maternal subjectivity in her mixed media exhibition that closed Thursday, Feb. 27

Masterfully aware of the space it takes up, “Umbilical Ouroboros” by artist Lauren Frances Evans wholly swaddles visitors up into its world through an intimate mixed media experience by inviting reflection on the complicated relationships between creator and offspring, conception and existence and earth and the divine.

“Umbilical Ouroboros” was located in the George Caleb Bingham Gallery, which is overseen by the MU School of Visual Studies. Upon entering the space, visitors were met with six sculptural works, three digital videos, two photographic works, one drawing and one mixed-media framed work.

“I’ve been sitting on this title ‘Umbilical Ouroboros’ for a little while,” Evans said. “I thought of it more as like a symbol for connecting, the physical and the immaterial, or these different aspects of ourselves and our connection to our origins.”

As an educator, advocate and artist, Evans said she has always been inspired by the human experience, particularly motherhood. Upon moving to her current home in Birmingham, Alabama, Evans became involved with the local birthing community. Her connections to Birmingham Born, an organization of midwives, doulas, childcare experts and expecting parents who support each other in pregnancy, allowed her to learn about the multiplicity of roles and experiences involved in birth.

“My friend, who’s a midwife, was like, ‘Hey, my client doesn’t want her placenta. Do you want it?’” Evans said. “And I was like, ‘yes.’”

This access to raw materials is infused in much of her creative process for “Umbilical Ouroboros.” This unfiltered, human impact makes pieces like “Holy Wound,” a photograph of a placenta printed on silk, and “Monument Letdown,” a framed work that showcases a figure made of dehydrated human breast milk, all the more powerful. Both pieces allow the viewers to consider the multitude of experiences visible in each one.

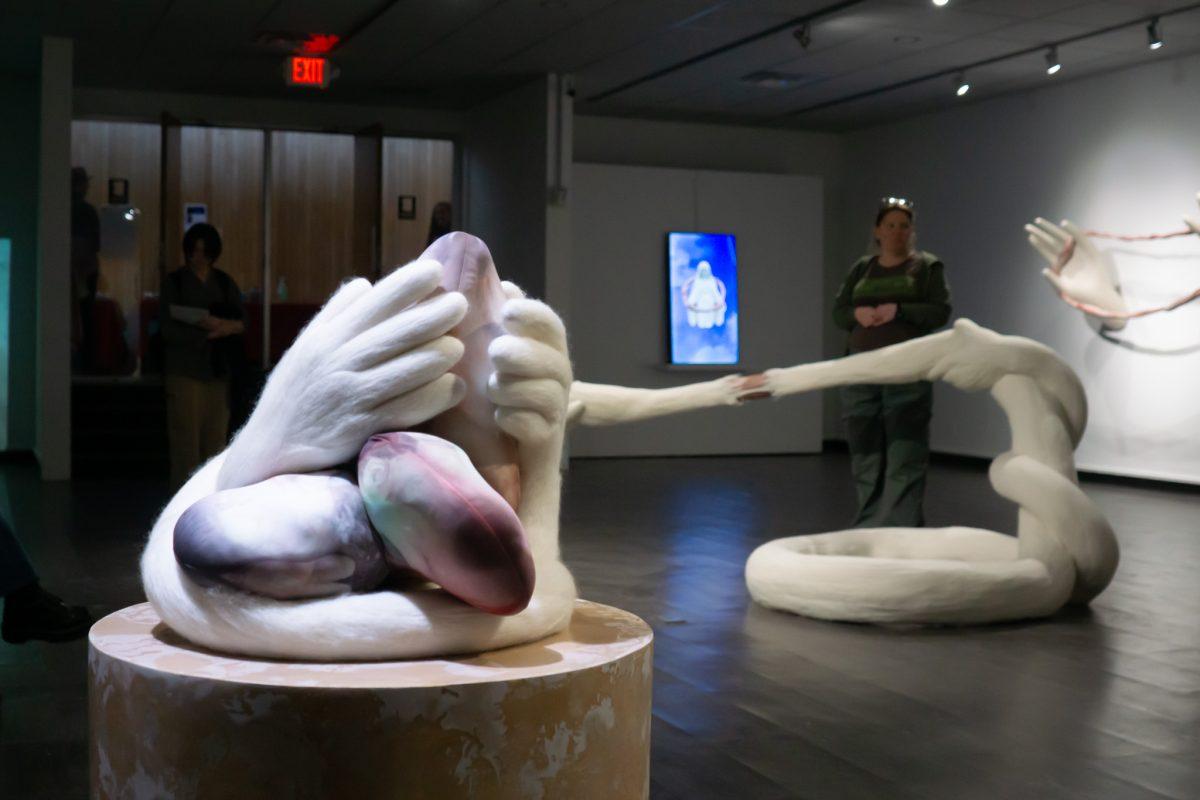

The exhibit’s warm color palette, awash with fleshy pink and red tones accompanied by fuzzy sculptures, generates a sense of calm and familiarity. One can’t help but wonder: ‘Is this what the inside of a mother’s womb is like?’ Stark imagery of the Virgin Mary, exploration of the human body during birth, and ominous, ringing bell tones may be slightly unsettling when consumed separately. However, Evans has created an environment where together, these elements foster an oddly comforting sense of maternal security and groundedness.

Spread across the floor of Bingham Gallery are three larger-than-life needle-felted wool sculptures. “In Limbo,” “As Above, So Below” and “To Have and To Hold” are in unique collaboration as they stretch and pull and wrap around each other, seemingly infinite in their movement; the end and beginning of each sculpture are impossible to locate.

“That concept of ‘As Above, So Below,’ is this kind of correspondence between the physical and the metaphysical,” Evans said. “Becoming a mother was a huge paradigm-shifting experience for me to live and embody this concept that I’ve had of my connection to the divine, or [exploring] what that means.”

“As Above, So Below” appears as a human hand, reaching upward toward something, or perhaps someone, unknown to the viewer. The sculpture is grounded by a human foot, decisive in its placement on a mat of faux grass. The two elements are connected by a knot, wrapping around itself and intertwining, reminiscent of certain spiritual beliefs of life after death and the interconnectedness of body and spirit.

Installed on a nearby wall, “First Position” was inspired by the children’s game cat’s cradle, which involves looping a piece of string around one’s fingers to create different patterns.

“Physiologically, an umbilical cord connects to the baby’s belly button, and then to the placenta, which is attached to the mother,” Evans said. “And that was interesting to me, like a way to honor that connection, rather than necessarily the thing that’s on either side of it.”

“First Position” features two oversized human hands, which are also made of needle-felted wool, stretching out toward the viewer. A disembodied umbilical cord, made of printed lycra fabric and stuffed with fiberfill, is looped between the pinky finger and thumb of each hand. The hands are oriented with palms up in first person point of view, as though the viewer is holding the umbilical cord.

Throughout the exhibit, Evans works to evoke a deep sense of self for viewers and encourages them to contemplate their relationship with their own mother’s birth experience.

Tucked away in the corner of the gallery and projected on the wall is “Indwelling,” a 40-minute digital video that plays on a loop. The video shows the perspective of a mother looking down on her pregnant belly, as visual effects cause it to appear hazy and swelling with breath.

“I made [‘Indwelling’] while I was pregnant with my first daughter, and then I didn’t finish it until she was a couple years old,” Evans said. “[Giving birth] was the most embodied experience I’ve ever had, like the most in my body I’ve ever felt.”

Evidently, much of “Umbilical Ouroboros” is inspired by the parallels between Evans’ journey through motherhood and the evolution of her Christian faith.

“Council of Mothers” features three Virgin Mary figurines that Evans found, each adorned with their own hand-sculpted, copper umbilical cord. While notably smaller in size than its companions in the exhibit, the delicate femininity of this sculpture offers a change in perspective and a more tangible, relatable way to conceptualize broad concepts of womanhood.

“I have found myself kind of thinking about [the Virgin Mary] and what her experience might have been as a human rather than as this holy figure,” Evans said.

In “Umbilical Ouroboros,” Evans expertly plays with scale and perspective to create and resolve tension between her mixed media works of art in a way that mirrors the harmonious dichotomy of her motherhood experience. Her internal conflict becomes palpably external as she urges viewers to reckon with the responsibility of creation, the enigma of existence and to ask if what physically tethers us to life on earth is strong enough to keep us here.

“Not everyone is gonna give birth, necessarily, but we all were born somehow knowing that it connects to all of us,” Evans said. “And it’s such a universal experience in some ways, just how we come into the world, and I think it is so meaningful.”

Edited by Mikalah Owens and Ava McCluer | [email protected] and [email protected]

Copy edited by Claire Bauer and Natalie Kientzy | [email protected]

Edited by Emilia Hansen | eh[email protected]

Edited by Emily Skidmore | [email protected]