Director Laura Casabé tells the story of trans activist Claudia Pía Baudracco in this compelling and pertinent documentary

The legacy of Claudia Pía Baudracco will forever be preserved in filmmaker Laura Casabé’s “Family Album,” a strikingly relevant and deeply empowering documentary that tells the story of one of the women who spearheaded the fight for transgender rights in Argentina.

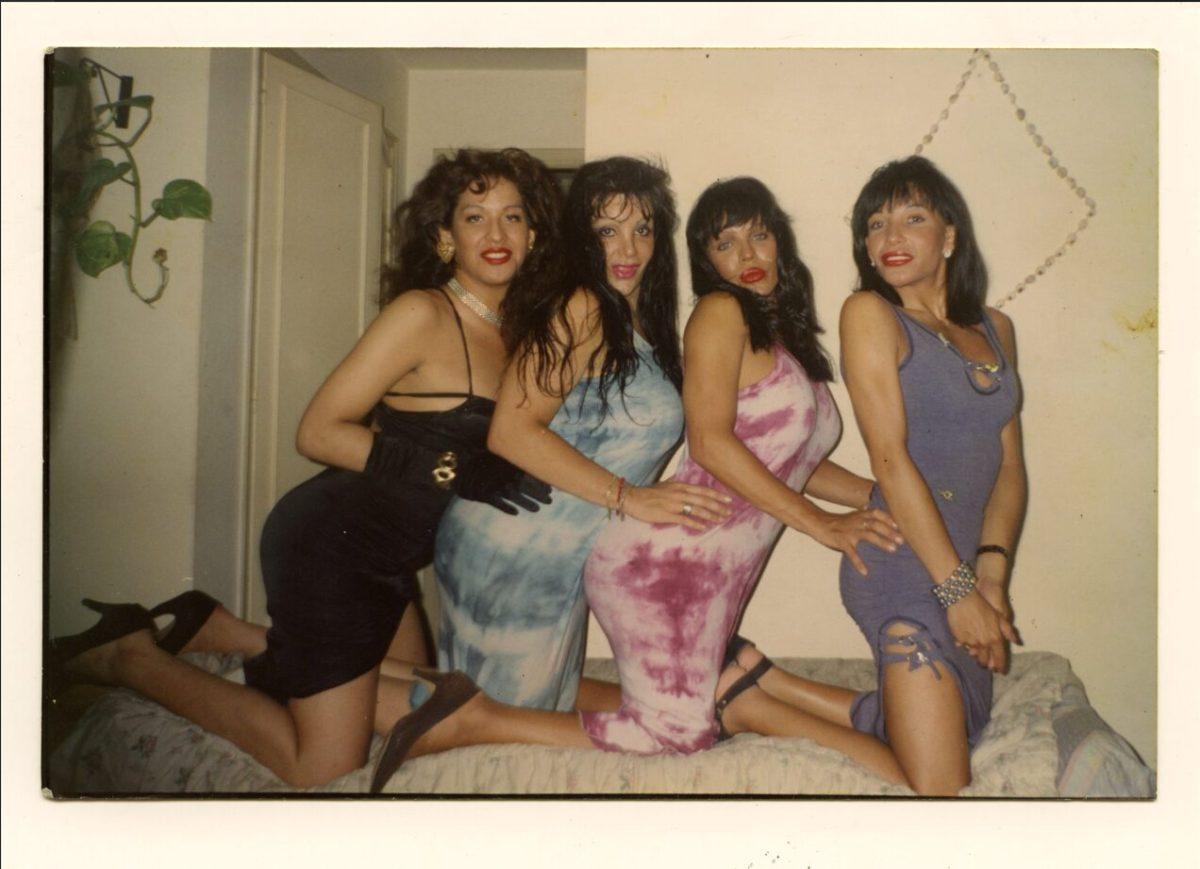

The basement of María Marta Aversa, one of Baudracco’s oldest and closest friends, becomes the anchor point of this film as it opens with a group of women sorting through Baudracco’s belongings. Boxes upon boxes are carried up the stairs and unpacked, as the kitchen table becomes a living museum. With each newly discovered article of clothing, trinket and beauty product comes a fresh memory of the life Baudracco led.

Through a masterfully crafted balance between intimate interviews with those closest to the activist and archival photos and video, the audience gets to know Baudracco well.

Born in 1970 in the Córdoba province of Argentina under a military dictatorship — a time of immense political and economic instability and human rights violations sanctioned by the Argentine government — Baudracco fled to Europe when she was a young teenager. Because of Argentina’s discriminatory legislation against trans people, she was not alone in her pursuit of the protection offered by the progressive gender identity laws in Italy. She lived and worked with several other trans individuals from Argentina during her time there in the 1980s.

Combining photos found during the archival process with sentimental narration, Casabé artfully contrasts the freedom Baudracco and others had in Italy with the criminalization of existence they experienced in Argentina, where Baudracco returned in the mid-1990s.

“Family Album” exposes the cycles of structural violence against trans people in Argentina that had been perpetuated by discriminatory legislation for decades. Trans individuals had no economic, political or social autonomy, causing Baudracco, along with many others, to turn to sex work as a means of survival. They often lived in isolated neighborhoods for protection and community, and some were victims of police brutality.

Inspired by their experience of political liberation in Italy, Baudracco and María Belén Correa, whom she met in Italy, formed the Asociación de Travestis, Transexuales y Transgéneros de Argentina, which translates to the Association of Travestis, Transexuals and Transgender people of Argentina. They soon began relentlessly advocating for trans rights in Argentina.

Themes of chosen family and the power of collective resistance are at the forefront of the rest of the film.

In one example, the audience watches as Baudracco and Correa remain steadfast and calm in a clip of a talk show interview full of microaggressions. Baudracco’s truly captivating, resonating way with words and passion for education strikes the interviewers. This momentum catapults both the film and the trans rights movement forward.

Later in the film, Baudracco is falsely arrested on drug charges. Her lawyer, Ángela Vanni, believed it to be a ploy orchestrated by the Argentine government to crack down on the movement. However, it did the exact opposite.

While imprisoned, Baudracco began organizing with fervor. She sent correspondence to trans rights activists working in other Latin American countries and the United States. She earned her high school diploma and led focus groups with other people who were incarcerated.

She analyzed and annotated a copy of the Penal Code of Argentina, a document given to her by Vanni, that detailed exactly what the crimes and punishments were for transgender and gender-nonconforming individuals. The film obtained Baudracco’s copy, focusing for several beats on passionate scribbles in the margins, fervent underlines and an outline of a plan to repeal.

Casabé does not shy away from discussing the lack of access to healthcare that trans people like Baudracco faced during the early 2000s in Argentina. The film adopts a somber tone as Correa reflects on the community’s reliance on dangerous, at-home procedures involving liquid silicone injections, which were administered by individuals without medical training. Correa describes how saddening and frustrating it was to lose people to complications that were the result of medical discrimination.

After Baudracco was released from prison, she introduced the Gender Identity Law into the Argentine National Congress.

The law would permit any individual over the age of 18, or minors with parental consent, to “request an amendment to his or her records in the civil registry in regard to his or her sex, name and image when it does not coincide with his or her own perceived gender identity.” Additionally, individuals over the age of 18 could receive subsidized access to gender-affirming care without court authorization.

It would be a huge feat for Argentina if passed, and Baudracco fought tirelessly for the implementation of the bill.

Over the course of the next several months, she spent the days traveling from province to province, empowering people to organize themselves and demand autonomy over their bodies from the government. She spoke in front of Congress. She led protests and demonstrations. TV broadcasts included in the film show throngs of people marching down the streets of Buenos Aires, clad in matching blue and pink shirts.

As the film progresses, Casabé works to build an impending anxiety in the audience, as the interviews with Correa, Aversa and others that fought on the frontlines with Baudracco become increasingly shorter and more emotional. The interviewees begin to speak in curtailed sentences, as if at a loss for words.

They describe Baudracco’s delicate relationship with sobriety and her use of drugs and alcohol. They recall stretches of days and nights where the activist would not sleep in her tireless brigade for trans rights. Painfully, the viewer comes to understand that Baudracco was fighting for rights to life-saving healthcare that she needed.

Just short of two months before the Gender Identity Law passed — almost unanimously— in Congress, Baudracco died in her home in Buenos Aires on March 18, 2012. She was 41.

“Family Album” is an undeniable proclamation of Baudracco’s life and legacy. Casabé shows the audience that she wasn’t just a trailblazer; she was an intelligent woman who was deeply in touch with her emotions, a fierce friend to every soul that crossed paths with her, the voice of a community in need and above all: proud.

Casabé has unearthed a conversation between the past and the present that clues us to look toward the future. As protestors continue Baudracco’s fight in 2025, they march outside Argentina’s government buildings chanting, “Claudia Pía! ¡Presente! ¡Ahora y siempre!” Claudia Pía! Present, now and forever!

In Buenos Aires, March 18 now commemorates the Day of the Promotion of the Rights of Trans People.

You can keep up with The Maneater’s 2025 True/False Film Fest coverage here.

Edited by Alyssa Royston | [email protected]

Copy edited by Natalie Kientzy | [email protected]

Edited by Emilia Hansen | [email protected]

Edited by Emily Skidmore | [email protected]