Lawyers have adopted a new strategy in jury selection, turning to social media websites such as Facebook and Twitter to find out information about potential jurors during the voir dire process.

This practice is well heard of among lawyers, according to Tom Neill, an attorney and MU graduate who co-authored the “Voir Dire and Jury Selection” chapter of the Missouri Civil Trial Practice.

“If you’ve got their names, then certainly you’re going to Google them up,” Neill said. “It’d be silly not to.”

In many cases, lawyers simply do not have time to carry out this form of research, he said.

“They bring in 36 or 42 or however many potential jurors (for a civil trial),” Neill said. “If you don’t find out who those people are until that morning, and you’re supposed to have it all done by the end of the first day, you might not have the opportunity to do much ‘Facebooking’ about a person.”

Defense attorney Jennifer Bukowsky uses social media to research her juries in every trial.

“We look for indications a juror would be biased one way or another on our particular case,” Bukowsky said in an email. “If a person supports marijuana legalization, that person may be good to have on a drug possession case. If a person is a retired police officer, that person may be bad to have on an assault of a law enforcement officer case.”

During a sexual assault trial last year, Bukowsky used Facebook to discover that one juror, a white female, was in several pictures with a black male. Since Bukowsky’s client fit the latter description, she wanted to keep the woman on the jury because the pictures showed she was not racist. The juror was eventually struck and the trial ended in a hung jury.

By researching a potential juror and finding a conflict of interest for the case, a lawyer is able to strike that person from the jury for cause, which Neill said is important, because attorneys each receive unlimited strikes for cause in jury selection. By proving the bias, the lawyer does not have to waste one of only three preemptive strikes he or she will receive.

On the flip side, Neill said lawyers look to find jurors who might be more sympathetic to their clients while conducting this research as well.

Some judges and lawyers do not support the use of social media to choose jurors, believing it is invasive. Bukowsky said she believes these lawyers do a great disservice to their clients.

“If you want to effectively and zealously represent your clients, you need to keep up,” Bukowsky said.

Graduate student Amy Sestric said she has never heard of this practice but sees how it would be useful.

“I think it’s cheap and reasonable as long as you aren’t crossing any ethical lines,” Sestric said.

Any information found on a social media site about a juror, a lawyer could bring up in questioning, Neill said. He said on the social media site, someone will likely see a more candid response about what the person believes.

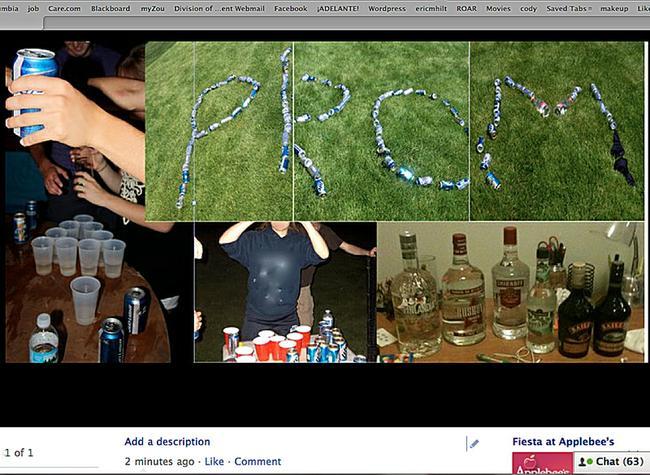

“A person might be somewhat uncomfortable answering your questions in front of other potential jurors,” Neill said. “So, when they might give you one answer in the courtroom, perhaps you’re getting an answer that is less filtered when they post it on their Facebook page.”